Sigismund Sigurd Lohde’s acting career was abruptly cut short by the Nazis because he was Jewish. After several places of refuge, he felt safe in British asylum. Like thousands of other refugees from Germany and Austria, he was bitterly disappointed there. In 1940, the British government deported him on the HMT Dunera to Australia, where he remained until 1954 after the end of his internment and army service. His story has been preserved in documents and memories of the artist.

Peter Dehn, November 2025.

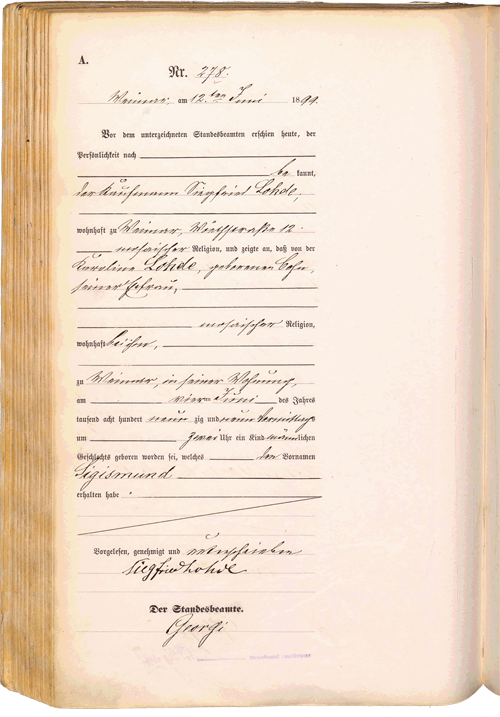

On June 12, 1899, Jewish merchant Siegfried Lohde registered the birth of his fourth son, Sigismund[1] Weimar Registry Office. Birth record no. 278 dated June 12, 1899, via Ancestry., on June 4, 1899, at the Weimar registry office.

The Lohde family

Siegfried Lohde was born on October 25, 1865, in Danzig. He settled in Weimar (Thuringia). He married Karoline (“Lina”) Cohn (born on March 11, 1874, in Bremen) in Berlin on June 14, 1894[2] Weimar Registry Office, marriage record no. 584 dated June 14, 1894, via Ancestry.. Siegfried ran a shop for “men’s and boys’ fashion, Parkstr. 1[3] Weimar address book, 1899, via ancestry. Today: Puschkinstrasse 1. Wikipedia entry on the building, accessed on August 15, 2025.” in the Thuringian city of classics. The family lived at Wörthstraße 12. Later, the company moved to a Renaissance building at Kaufstraße 15[4] Wikipedia on Kaufstraße, now a cultural monument, accessed on August 15, 2025. and the family moved to Prellerstraße 1[5] Address books for Weimar, 1899 and 1906, via Ancestry.. Siegfried was also co-owner of a residential and commercial building at Schillerstraße 16[6] Weimar City Archives, Files of the Building Authority, reference number II-8-284, Thuringia Archive Portal, accessed on September 20, 2025. in Weimar.

He was co-founder of the Israelite Religious Association[7] See Lernort Weimar. Traces of Jewish Life in Weimar and Jewish Places about the Israelite Religious Association Weimar, accessed on October 25, 2025. See Erika Müller, Harry Stein, Jewish Families in Weimar (Weimar City Museum, 1998). in Weimar. Since 1903, this association had been organizing religious education for the children of its 25 members, in which at least one of Lohde’s sons (probably Sigmar) participated in April 1904. The association also organized religious services on the high holidays.

The birth certificate from the Weimar registry office.

All four of the couple’s sons were born in Weimar and registered at the registry office as “Jewish” – like their parents. They lost their father at an early age; Siegfried died on July 3, 1915 in Weimar[8] Weimar Registry Office, death record no. 423 dated July 5, 1915, via ancestry.. Their mother Karoline was left to care for three sons, who were between 16 and 18 years old at the time.

Eduard Siegbert, born on June 18, 1895, died in childhood on November 3, 1896.

Sigmar was born on March 23, 1897. He moved to Berlin, where he briefly shared an apartment with his mother Lina and younger brother Gerhard at Schöneberg, Frankenstraße 5[9] Berlin telephone directory 1931/32 via ancestry., in the early 1930s. He most recently lived in Vienna, Kohlmarkt 5/3[10] See Lohde/Gork family tree via ancestry.. Frankenstraße 5[/ref] , and worked as a sales representative. He was deported to Auschwitz on July 17, 1942.

The third son, Gerhard, born on May 19, 1898, was married twice. He died at the age of only 37[11] Birth and death dates of Sigurd Lohde's brothers via ancestry. on January 22, 1936, in Stendal Hospital after being forced to do unskilled labor in road and railway construction since 1933. The planned Stolperstein[12] Stumbling stone for Gerhard Lohde in Tangerhütte (Saxony-Anhalt), Schillerstraße 4. dedicated to him will bear the inscription: “Worn down by hard labor and bullying.” He left behind a son from his second marriage to Elise Hedwig Elisabeth Kupferschmidt (June 6, 1903 – August 5, 1986) named Hans-Georg Siegfried Berthold[13] See Lohde/Gork family tree, op. cit. (October 19, 1931 – April 9, 1983).

Their mother Karoline had moved to the German capital in 1928, where her sons worked. She fled from the Nazis to Vienna in 1933, where she lived with her son Sigmar, who had lost a leg in World War I, in Hockegasse[14] Address and telephone directories for Vienna from 1938 to 1940, via ancestry. (13th district). Later, the Nazis forced her to move to a “Jewish apartment” at Kohlmarkt 5/7. On July 10, 1942, she was deported to Theresienstadt and from there sent to her death on September 23, 1942, on transport Bq/1782 to the Treblinka extermination camp[15] Transport list from Theresienstadt via Arolsen Archives, accessed on August 15, 2025..

Karoline Lohde. Source: Lohde family archive.

Early career as an actor

Sigismund (his officially registered only first name) was the youngest Lohde son. He was supposed to “join his uncle’s bank.” As the “black sheep of the family,” he made his debut as an actor while still a schoolboy on June 18, 1916, at a vaudeville show at the restaurant “Deutscher Kaiser” in Bad Berka an der Ilm, according to a note in the Straschek collection[16] Günter Peter Straschek. Collection of documents commissioned at Philipps University of Marburg for an unpublished encyclopedia of filmmakers in exile. The collection of material on Sigurd Lohde comprises 70 unnumbered sheets, mainly notes without evaluations or source references, as well as correspondence. Inventory EB 2012/153.D.01.2005 in the Exile Archive 1933-1945 of the German National Library in Frankfurt/Main, DNB entry. Wikipedia entry on Straschek, accessed on July 1, 2025.. He must have made a good impression there and later at an audition in Berlin. In April 1917, he was accepted as a scholarship student at the Marie Seebach School[17] Today: Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch. Lohde is not mentioned in a list of graduates. of the Königliches Schauspielhaus Berlin[18] Straschek Collection aao.. His training was interrupted by the World War; Lohde served on the Western Front in 1917/18, ultimately as a lieutenant[19] Ibid. and Lohde's statements in his Australian military file, Australian National Archives NAA_ItemNumber6254965.. After further training with Leopold Jessner[20] Wikipedia entry on Leopold Jessner, who was artistic director of the Schauspielhaus Berlin from 1919 to 1928, accessed on July 10, 2025. (1878–1945), Lohde took on various engagements under his birth name, Sigismund Lohde: in 1920/21 he worked in Bremerhaven, then in Frankfurt am Main[21] Straschek Collection aao.. “The theater ensemble was complemented by the engagement of Sigurd Lohde as its first character actor and director – most recently active at the Reinhardt stages in Vienna,” reported a Graz newspaper[22] “Arbeiterwille” Graz on August 28, 1928, page 4, via Anno (Austrian National Library). in August 1928. In October 1928, he staged “Oktobertag[23] Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, October 13, 1928, page 8, via Anno” (October Day) there, and in June 1929, “Rivalen[24] Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, June 2, 1929, page 17, via Anno.” (Rivals) by Zuckmayer.

In Breslau, he had filed a lawsuit[25] See also German Federal Archives, BArch R 56-III/1138. against his summary dismissal in 1924. A publication by the local Volksbühne theater announced the reappointment[26] „Kunst und Volk. Blätter der Breslauer Volksbühne e.V.“, no.1 1926/27“, page 31 via Deutsches Zeitungsportal. of “Sigurd Lohde from the Schauspielhaus Zurich” at the beginning of the 1926/27 theater season. In 1928, he lived there at Goethestraße 53[27] 1928 handbook of the German Stage Employees' Cooperative (GDBA), page 304, via ancestry..

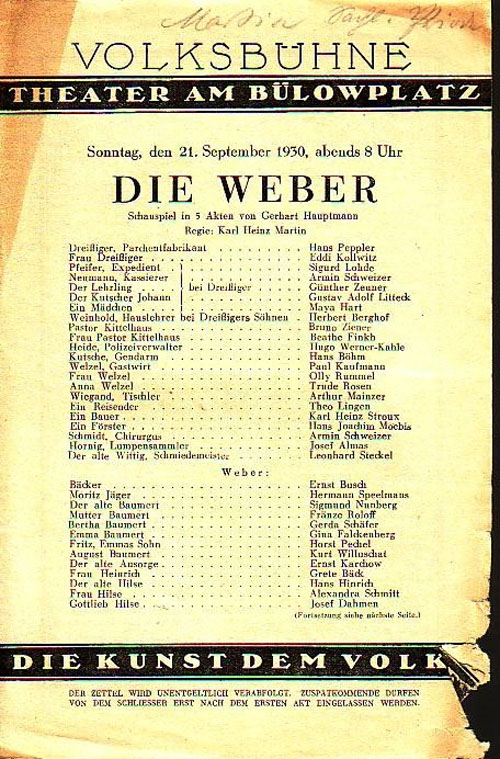

In Hauptmann’s “Die Weber” (The Weavers), Lohde played the clerk Pfeiffer at the Berlin Volksbühne in 1930.

On Berlin stages

From 1929 to 1932, he was a member of the ensemble at the Berlin Volksbühne. There he appeared in Franz Molnar’s „Liliom“ alongside Hans Albers, Therese Giehse, and Bertha Drews, among others. In a vaudeville show, he was part of the “Seemannsquartett” (Sailors’ Quartet) with Ernst Busch and others. He also performed in “Kamrad Kasper[28] Volksbühne am Rosa Luxemburg-Platz, Season Chronicle 1930 to 1940, accessed on August 20, 2025.” by the Low German author Paul Schurek (with music by Hanns Eisler) with Busch and Drews. He also appeared on other stages in the capital; his performance in “Büromädels” (Office Girls) at the Lessing Theater “deserved mention,” according to the Berlin newspapaer “Börsenzeitung[29] Berliner Börsen-Zeitung on November 18, 1924, page 41, via Deutsches Zeitungsportal.”.

Sigurd Lohde also worked for the young medium of radio. He is known for his participation in 13 productions[30] ARD radio play database at the German Broadcasting Archive, accessed on August 25, 2025. recorded between 1927 and 1932. In 1929, the children’s program “König Drosselbart” (based on the fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm „King Thrushbeard“) was produced for the Vienna radio station with Lohde as the court jester[31] Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, January 5, 1929, page 11, via Anno.. He played several leading roles in radio plays, including the theater director in Franz Molnar’s “Das Veilchen” (The Violet) and the administrator in Goethe’s „Stella“ for Berliner Funkstunde. The program sections of German and Austrian newspapers also refer to his “Heitere Stunde” and the comedy “Kater Lampe” on the Breslau radio station.

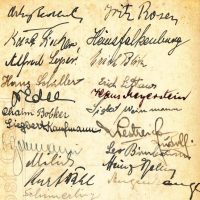

At that time, he served as an employee representative in the Genossenschaft Deutscher Bühnenangehöriger[32] GDBA Handbook 1931, page 304. (GDBA); Cooperative of German Stage Employees) at the Volksbühne. Among other things, he was appointed head of a working group of the Film Association, which in 1932 called on film distributors and cinema operators to “release all completed films onto the market in view of the extraordinary shortage of films,” reported a trade journal[33] In “Der Schrei nach dem neuen Film” (The Cry for the New Film), Kinematograph, July 29, 1932, page 1, via Anno..

In 1931, he lived with his mother at Frankenstraße 5[34] GDBA Handbook 1931, page 303 via ancestry, and autograph contact in “Mein Film” from issue 358, page 16, via Anno.. In telephone directories from 1934 and 1935[35] Berlin telephone directory, 1934, via Ancestry., there are entries with the first name Sigurd and the occupation listed as actor and director at Barnayweg 1 (today Steinrückweg) in the Wilmersdorf Künstlerkolonie[36] Wikipedia on the artists' colony, which was built in 1927 by the GDBA and the Schutzverband deutscher Schriftsteller (Protective Association of German Writers) to provide affordable housing for artists without social security, accessed on September 22, 2025. (artists’ colony).

Early film work

Sigismund Lohde got his first film roles in 1931. He is listed among 60 “uncredited[37] “M” in the film database IMDB, accessed on 15 August 2025.” actors in Fritz Lang’s “M – A City Searches for a Murderer.” As Jim in the artist film “The Leap into the Void,” he was listed third in the cast. This production was shot in Paris[38] At that time, films were often shot in several languages simultaneously. Wikipedia entry on “Der Sprung ins Nichts” (The Leap into Nothingness), the German cinema market version of “Halfway to Heaven,” accessed on August 15, 2025. by the US company Universal. “The world of international criminals is excellently portrayed by Sigurd Lohde (as Fred Patterson, a rich American, dunera.de), Ernst Stahl-Nachbaur, Fritz Klippel, and Leonhard Steckel,“ praised a reviewer[39] Hallesche Nachrichten, December 24, 1931, page 17, via Deutsches Zeitungsportal. of the film ”Der Draufgänger” (The Daredevil), which was released at Christmas 1931 with Lohde alongside UFA star Hans Albers.

Two “Prussia films” followed in 1932, in which Lohde played high-ranking officers. In “Tannenberg,” he played Russian General Samsonov. This film glorified Field Marshal von Hindenburg[40] Wikipedia on Paul von Hindenburg, one of the co-inventors of the “stab-in-the-back myth,” which claims that the homeland betrayed its successful military leaders during World War I. Retrieved on August 25, 2025. and his 1914 victory over Tsarist Russia. Using the example of the now Reich President, a militaristic cult of leadership was propagated. A few months after the premiere, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Reich Chancellor—the next cult of leadership figure.

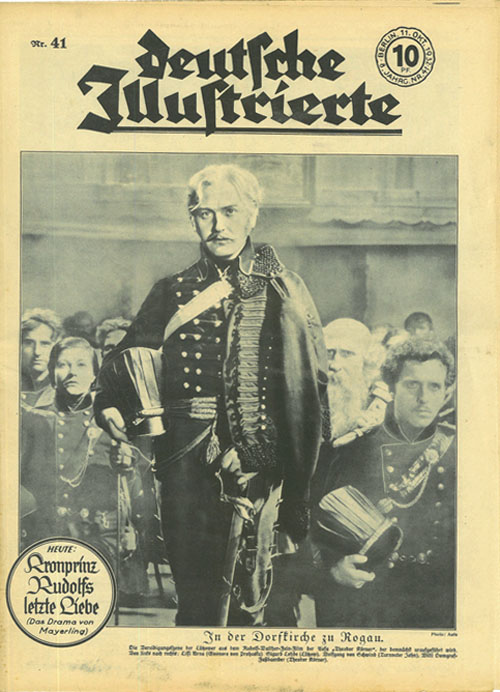

The biopic “Theodor Körner” premiered a few weeks earlier. In it, Lohde played Freikorps leader Lützow[41] Entry for the film “Theodor Körner” on IMDB, accessed on August 15, 2025. from the wars of liberation against Napoleon, also in anticipation of the Nazis’ nationalistic image of Prussia. This role landed Lohde on the cover of the right-wing magazine “Deutsche Illustrierte[42] The “Deutsche Illustrierte” No. 41 from October 11, 1932, has no article accompanying its cover photo. On page 2, “The Path to the People's Community” is evoked in the text with photos of a paramilitary labor camp and a paean to the “real people's army” of the imperial era. Issue in the Dehn Archive..”

Sigurd Lohde played minor roles in at least nine other German productions until 1933. The trade journal „Kinematograph“ mentioned his appearance as the third son-in-law in „Frau Lehmanns Töchter“ (Mrs. Lehmann’s Daughters) “merely for the sake of completeness[43] “Kinematograph” from June 11, 1932, page 2, via Anno., … because the role itself offers little opportunity to show anything greater or more remarkable.”

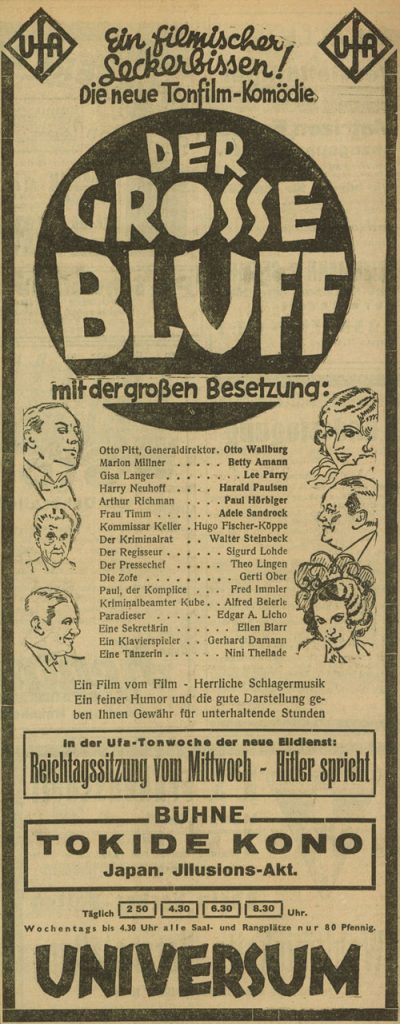

In the 1932 UFA comedy, Lohde played a director. (Cinema advertisement in a Nazi newspaper).

Source: Deutsches Zeitungsportal.

Sigurd Lohde in the role of Lützow in the film “Theodor Körner” as the title character (No. 41 b. October 11, 1932).

Source: Dehn Archive.

“Just for the sake of order…” as a potential son-in-law in “Frau Lehmann’s Daughters.” Sigurd Lohde in the left photo, back center. From “Das interessante Blatt”, Vienna, September 25, 1932. Source: Anno newspaper archive.

Forced to flee Germany

The Nazis did not thank Lohde for his quasi-ideological support. As a Jew, he was excluded from membership in the “Reichsfilmkammer[44] Wikipedia on the Reichsfilmkammer, accessed on August 16, 2025.”, which was synonymous to a professional ban. Lohde fought back against this with a letter to Goebbels that was as courageous as it was futile, according to a tradition passed down to Straschek, for which no evidence is available.

Lohde did appear in films that were ideologically close to National Socialism. However, Australian historian Cyril Pearl[45] Cyril Pearl, “The Dunera Scandal,” Angus & Robertson, 1983, page 22, does not cite any sources. was mistaken in his claim that Lohde received a letter of thanks from Mussolini for his leading role as Napoleon in the film “Hundert Tage[46] Cinegraph and Wikipedia on “One Hundred Days,” accessed on August 15, 2025.” (One Hundred Days). This film role was played by Werner Krauß[47] Wikipedia entry on actor Werner Krauß, accessed on August 15, 2025., who later became a Nazi film official and had previously appeared as Napoleon in that play on stage in Berlin. At the time of filming in late 1934, Lohde had already been banned by the Nazi film industry and was living in Vienna. However, he did play Mussolini’s power-political role model Napoleon in a production at the Deutsches Theater Brünn[48] “Neues Wiener Journal” on December 12, 1933, page 11 via ANNO. (Brno, Czech Republic) in December 1933. At this theater, the majority of “democratic plays were staged with considerably more care[49] Katharina Wessely, “Theater der Identität” (Theater of Identity). Radio Prague International on December 22, 2012, accessed on August 25, 2025..”

Theater and film work in Vienna

Sigurd Lohde had already moved to Vienna in June 1933[50] Straschek Collection aao. to escape the looming anti-Semitic persecution of the Third Reich and, of course, to find work in his profession. From 1934, a cinema magazine mentions Berggasse 6 in Vienna’s 9th district as Lohde’s autograph address[51] “Mein Film,” issue 440 (end of May 1934), page 9, via Anno. for the first time.

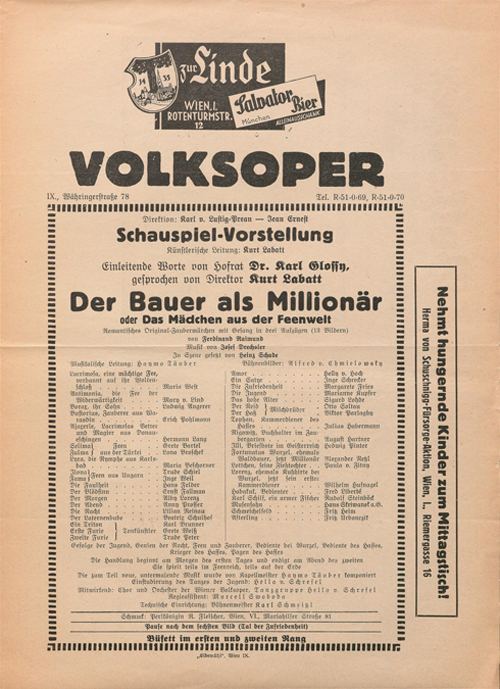

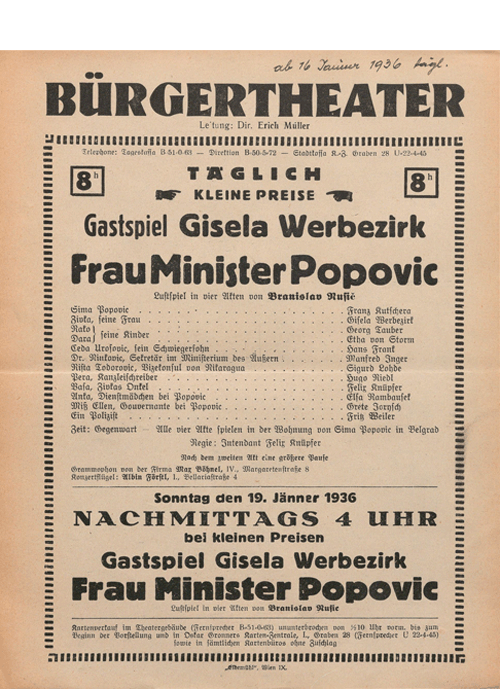

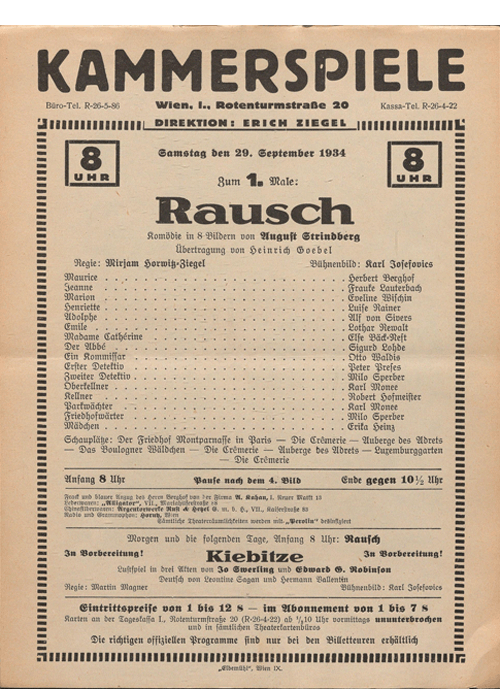

Among other roles, he played in the Vienna Volksoper’s production the role of “Das hohe Alter” (“The Old Age”) in “Der Bauer als Millionär” (“The Farmer as Millionaire”). At the beginning of 1934, he was engaged for the reopening production of the Raimund Theater’s[52] Kleine Volks-Zeitung, January 21, 1934, page 28, via Anno. “Die Wirtin von Venedig” (“The Landlady of Venice”); “great,” reported one newspaper. In 1934, he appeared as the “Abbé” in Strindberg’s „Rausch“ (There Are Crimes and Crimes) at the Kammerspiele, and in 1936 in “Die Schwester des Lords” (The Lord’s Sister) and “Frau Minister Popovic” (Mrs. Minister Popovic) at the Bürgertheater. A guest performance took him to Prague in November 1936; in Ibsen’s “Gespenster” (Ghosts), he appeared as a pastor alongside the refugees Tilla Durieux[53] See Wikipedia entry on Tilla Durieux, accessed on August 28, 2025. and Ernst Deutsch at the Neues Deutsches Theater[54] Wikipedia on the New German Theater, which existed in Prague from 1888 to 1938. Today, the building houses the Czech State Opera. Retrieved on August 25, 2025.. In 1937, a telephone directory entry listed his profession as actor in Vienna’s 19th district, Medlergasse 5[55] Vienna telephone directory, 1937, via Ancestry.. According to Straschek, Sigurd Lohde also worked as a physiotherapist in Vienna.

Sigurd Lohde performed at various theaters in Vienna and in guest performances.

“Peter, das Mädchen von der Tankstelle” (Peter, the Girl from the Gas Station) was his first film in Austria. He appeared four times in productions by Henry Koster[56] Wikipedia on Jewish director Hermann Kosterlitz, who made his career in Hollywood in the 1950s with comedies and the musical drama “One Hundred Men and a Girl.” (aka Hermann Kosterlitz, 1905–1988). For his last film of this period, “Bubi” (aka “Der kleine Kavalier”; The Little Gentleman), Lohde was listed third in the cast as a variety theater director.

For the Austrian theatrical release of “Mary Stuart” (directed by John Ford) in 1936, he lent his voice to Robert Barratt[57] See Deutsche Synchronkartei (dubbiong database; list for Lohde is incomplete), accessed on September 20, 2025. as Norton.

Just a piece of tin?

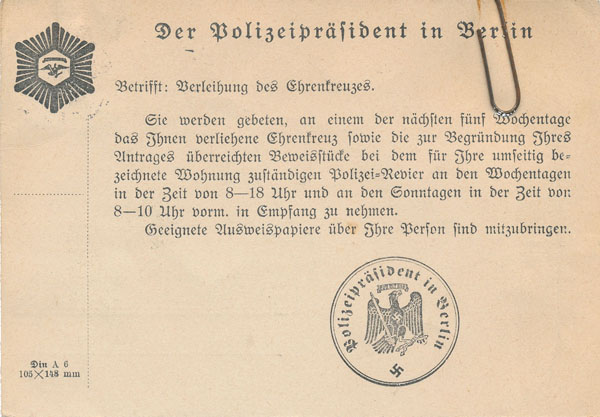

In Vienna, Lohde has become “the target of a nasty cynical joke,” Straschek noted: The actor was summoned to the German embassy[58] Straschek Collection aao., “where he was awarded the Cross of Merit 2nd Class, the so-called Hindenburg Cross, on behalf of Führer Adolf Hitler.”

The correct name for this medal is “Honour Cross of the World War[59] Wikipedia on the “Cross of Honor,” accessed on August 15, 2025.”. It was established by Paul von Hindenburg in July 1934 and was therefore also known as the “Hindenburg Cross.” Because Hindenburg, former field marshall of the Emperor and now Reich President and Hitler’s stooge, had already died on August 2, 1934, the medal was henceforth awarded “in the name of the Führer and Reich Chancellor.” This was in contrast to the awarding of orders, exclusively at the request of war participants. At least 8 million of these medals were distributed.

In 1934/35, persecution had not yet progressed to the point where Jews were excluded from receiving the medal. Many Jewish World War I veterans – and perhaps Sigurd Lohde as well – applied for the cheaply pressed and bronzed piece of metal.

Postcards such as this one, addressed to Leo Dehn, were sent to applicants inviting them to collect their Cross of Honor. Source: Dehn Archive.

Perhaps Sigurd Lohde believed, like tens of thousands of Jewish front-line soldiers and officers (among them Leo Dehn), that the cross would protect him from racist persecution. However, this hope proved to be illusory. The Lohde family suspects that Sigurd may have applied for the medal on behalf of his disabled brother Sigmar.

Escape from Vienna and Prague

According to Straschek, Sigurd Lohde set off for Prague via Ostrava and Liberec on March 11, 1938—the day before Austria’s annexation[60] Wikipedia on the “Anschluss” of Austria, accessed on August 20, 2025. by Nazi Germany. Hitler occupied the remaining Czech Republic[61] Wikipedia on the breakup of Czechoslovakia, accessed on August 15, 2025., which had been created as a result of the Munich Agreement of October 1938, in March 1939 and de facto incorporated it into the Nazi Reich as the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia[62] Wikipedia on the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, accessed on September 25, 2025.”. Thousands of refugees in the Prague exile were in danger of falling back into the hands of their persecutors. Sigurd Lohde was arrested and, according to reports, was only able to escape the Gestapo by jumping out of a window. In the summer of 1939, he managed to complete the next stage of his escape via Krakow to England[63] Straschek Collection aao..

In England

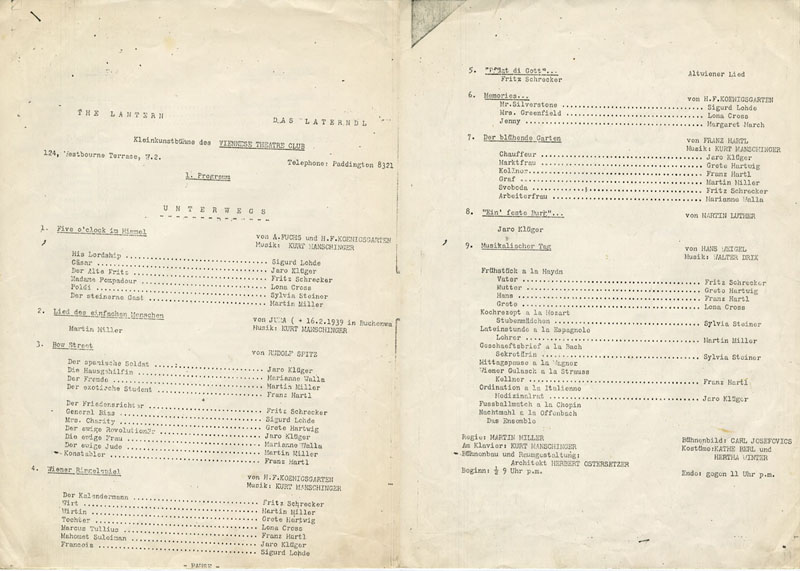

He found accommodation at 60A Boundary Road[64] Home Office index card for Lohde, via ancestry. in north London and worked for the German-language BBC radio station, among others. The first show by the Austrian-founded theater “Das Laterndl[65] Mark Piggott “A Beacon of Hope ...” University of London online, June 17, 2024, accessed August 15, 2025.” (The Lantern) was called ‘Unterwegs’ (On the Road) and premiered on June 27, 1939. In the first number of the cabaret revue, presented in English, Sigurd Lohe appeared as “His Lordship” at the top of the program sheet. The remaining numbers were performed in German; Lohde appeared in other roles. The British press praised the show concept[66] The Spectator on July 7, 1939, quoted in “A Light in Dark Times,” Exile Research Center, accessed on July 15, 2025., which was previously unknown there. “We should be grateful to Herr Hitler for the Lantern. Austria’s loss has been our gain.” He also appeared at the Deutsche Theater[67] Straschek Collection aao. in London. However, theaters and cinemas were closed at the outbreak of war.

Vienna in exile in London theaters: Sigurd Lohde played several roles in the first program of “Laterndl” (click on image to enlarge).

Source: Website A Light in Dark Times.

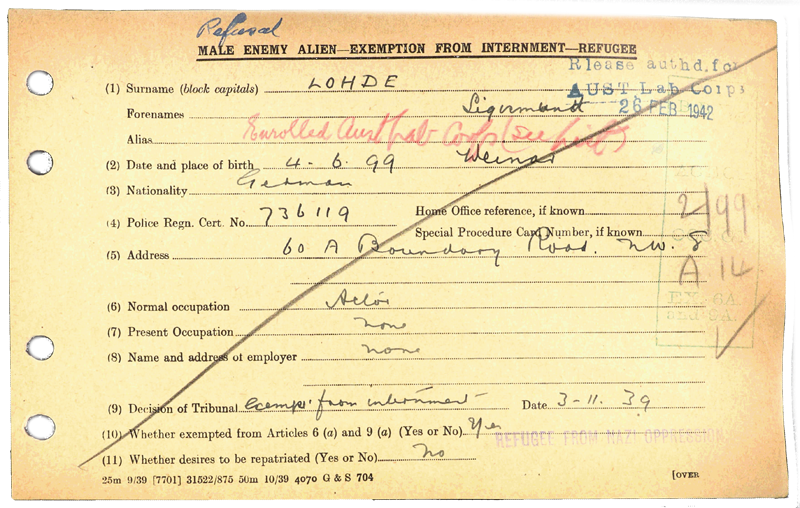

The British alien tribunal had confirmed Sigurd Lohde’s status as a refugee and he was “exempted from internment[68] Index card from the Home Office aao.” on November 3, 1939. Eight months later, this was no longer valid.

The short period between his arrival in Great Britain in summer 1939 and his arrest and internment on July 1, 1940[69] Australian personnel file for S. Lohde, NAA_ItemNumber9903925, via NAA. was naturally too short to establish himself in the country of asylum and make a lasting entry into the film industry. The only thing that can be verified with certainty is the war comedy “Neutral Port[70] “Neutral Port” in the IMDB film database, accessed on 15 August 2025.” with Lohde as the German consul. Straschek noted other productions, but there is no evidence of Lohde’s involvement in the relevant film databases. However, it may be that he had individual days of filming in small roles, so that his name is not documented[71] “Convoy,” “Sailors Three,” and “Night Train to Munich” in the British Film Institute database, accessed on August 15, 2025.. This applies to “Nighttrain to Munich” (Officer on the train), “Convoy,” and “Sailors Three,” among others.

“Wrong ship”? – Wrong enemy!

There are differing opinions about the circumstances surrounding Sigurd Lohde’s deportation to Australia. After his return, he himself told the Berlin newspaper „Telegraf“ that he had been sent “to Australia by mistake[72] Headline in “Telegraf,” March 1, 1955, page 3, source: Lohde family archive”. He should have been interned on the Isle of Man, he continued. However, in the port of Liverpool, there was “tremendous confusion” in “the days before Dunkirk,” and he was “literally forced onto the wrong ship” – namely the Dunera – by British soldiers. The claim that Lohde arrived at the port by taxi, carrying a ticket and “an official document,” in order to be transferred to the Isle of Man to work as an interpreter is hardly credible. Despite Sigurd’s protests, the guards[73] See Cyril Pearl aao. reacted “by lowering their bayonets and barking ‘Get going!’” in the direction of the Dunera. He said heprotested in vain with a hunger strike, because he was “not a prisoner of war, but a persecuted refugee,” as quoted by the Berlin newspaper[74] According to numerous autobiographical accounts, the internees only learned of their destination, Australia, when the journey took too long, the climate became tropical, and the Dunera made its first stop in Freetown (Sierra Leone)..

The decision of the British tribunal on November 3, 1939, to exempt him from internment was only valid until the beginning of July 1940.

Source: Sigurd Lohde index card from the Home Office via ancestry.

“Accidentally ended up in Australia.” Lohde on Lohde in the West Berlin newspaper “Telegraf” on March 1, 1955. Source: Lohde family archive.

These representations are incorrect. However, they have a very real background.

First of all: The departure of the Dunera has no temporal connection with “the days before Dunkirk.” The evacuation of Allied troops across the English Channel was completed on June 5, 1940[75] Wikipedia on the Battle of Dunkirk. The Dunera did not set sail until July 10, 1940., a month before the HMT Dunera departed Liverpool on July 10, 1940. Moreover, Dunkirk is located at the eastern end of the Channel. An evacuation by sea of more than 1,100 kilometers[76] See Sea Distances online, accessed on 25 August 2025. (597 nautical miles) from Dunkirk to Liverpool would have blocked valuable transport capacity for weeks and hampered the evacuation of Allied troops. Dunkirk and Dover are only 38 nautical miles apart, a tour of just a few hours.

„Economical with the truth“

The main reason for Sigurd’s “accidental” trip to Australia was his internment in the camp at the Lingfield[77] The small town is located in the county of Surrey, south of London. racecourse, which was only intended for short-term accommodation. Officers not only at this camp abused the trust placed in them by the internees and lied to “their” men in order to meet the requirements for “voluntary” registration[78] Around 1,000 internees from the British camp in Huyton were promised greater freedom and that their interned wives and children would follow shortly. Further migration, e.g. to the USA, was held out as a prospect. See Memorandum der Internierten von Camp 7. for overseas travel. In their memorandum on the Dunera voyage, the internees at Camp 7 Hay stated, among other things:

“The internees coming from the temporary camp Lingfield (about 350 on board H.M.T. ‚DUNERA‘) were promised that they were going to a more permanent camp in England. They were accordingly in no way prepared for a long journey overseas.”

So it comes as no surprise that Sigurd Lohde was not the only one expecting to be transferred via the port city of Liverpool to one of the camps on the Isle of Man. “ I do not believe this was ever a ‘mistake’ on part of the authorities as many claim, I think it is more likely a case of the Lingfield Camp commandant being economical with the truth,” comments British historian and son of a Dunera Boy, Alan Morgenroth[79] Email from Alan Morgenroth to dunera.de dated August 14, 2025..

No horse races took place during the war. Like Lingfield Race Course (photographed in 2011), many racecourses in Great Britain and Australia were used for military purposes and to house internees.

Source: Wikipedia, Sempre Volando.

Another consideration speaks against a “mistake.” A total of 13 lists of names were drawn up in several internment camps for transport on the Dunera. “Lohde, Sigismund 7992” is one of 300 names on list 7[80] See list 7 of the 12 of 13 embarkation lists in the NAA archive, NAA_657104_Liste7_300, accessed on February 17, 2024., which is assigned to the Camp Lingfield[81] The connection between List 7 and Lingfield is established by historians Alan Morgenroth and Rachel Pistol in “The Dunera Boys ... Who, when and why?” In “Dunera News” No. 109, page 10f.. The deportation of this group was therefore part of the British authorities’ plan to send internees overseas, and not a “mistake.” Given the lies told by the camp officers, it is not surprising that the internees from Lingfield were surprised to be taken on an ocean liner instead of a smaller ferry to the Isle of Man. Lohde’s remark about the “welcome” with bayonets at the ready, forcing him aboard the Dunera, is consistent with other internees’ accounts of the situation in Liverpool harbor and the reception on the Dunera.

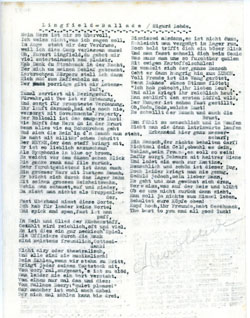

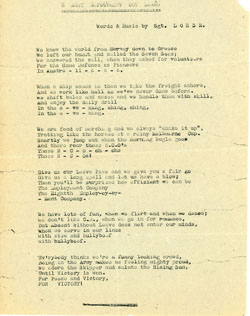

The fact that Sigurd Lohde was detained at Camp Lingfield is also confirmed by himself. In the “Lingfield Ballade[82] Sigurd Lohde: “Lingfield Ballade,” bilingual original. Inventory number 4097 of the Jewish Museum of Australia.,” he described everyday life at the “Lingfield health resort” in ironic rhymes and mocked the guards. The bilingual text concludes with the optimistic call:

„Kopf hoch, ihr Freunde, habt Geschmack

The best to you and all good luck!“

(Click on image to enlarge. Source: Courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Australia, inventory no. 4097).

Opponents: Winston Churchill and …

… the liberal MP Eleanor Rathbone.

Source: Wikipedia.

„Collar them all“

This slogan, attributed to Winston Churchill, sums up British internment and deportation policy in mid-1940. The occupation of the Arandora Star revealed part of the system used by the British authorities to occupy the five deportation transports. On July 9, 1940, Minister of Shipping Ronald Cross[83] Minutes of Question Time in the British House of Commons on July 9, 1940, accessed on August 20, 2023. responded to questions in the House of Commons on the occasion of the sinking of this second deportation transport to Canada by stating, „that all the Germans on board were Nazi sympathizers and that none came to this country as refugees.”

To support the claim that only enemies of Britain had been deported, Cross used the classification of many foreigners as Nazis in category “A.” On board the Arandora Star, one in three Germans and Austrians had been proven to have been persecuted by the Nazis as Jews or for political reasons. Many had been imprisoned in concentration camps after the pogroms in order to force them to leave the country and confiscate their assets. The deliberately false classifications[84] The decisions of the tribunals “at least reflected the opinion of the social class from which these King's Counsels (advisors to the king) came.” Several tribunals used inadequate guidelines to “exercise their anti-Bolshevik bias by declaring all veterans of the International Brigades who had fought fascism in Spain to be suspects.” This is the assessment of Canadian internee Eric Koch in “Deemed Suspect. A Wartime Blunder,” Toronto 1980, pages 9/10. made by the British placed perpetrators and victims on the same level, shaped the fate of thousands of refugees in England, and meant death for many victims of the Nazis. This leaves behind a great sense of unease.

The deportation of thousands of Nazi victims to Canada and Australia was neither in general nor in individual cases a British “mistake,” but part of the mass deportations of undesirable foreigners ordered by Churchill. No one was sent “on the wrong boat.”

The liberal parliamentarian Eleanor Rathbone[85] Wikipedia on Eleanor Rathbone, accessed on September 10, 2025. (1872–1946) had already sharply criticized[86] Minutes of the House of Commons from July 10, 1940, accessed on September 10, 2025. Winston Churchill’s government in the British House of Commons on July 10, 1940, the day of the Dunera’s departure, for the deportation of “those who have been pronounced by the tribunals to be victims of Nazi oppression. (…) If you throw your net round all the fish and draw them in, though only a very small minority of the fish are dangerous and suspicious people, you will at any rate get hold of those you want. But you do not get hold of all the dangerous people.”

“The British government has declared war on the wrong people,” British social scientist Francois Lafitte[87] Francois Lafitte „The Internment of Aliens“ was the first book about Britain's treatment of the refugees. It was published in England in September 1940, so it could not take into account the events on the Dunera and in the camps. attested to Winston Churchill and his Government in “The Internment of Aliens,” the first book on internment and deportation, which was published in as early as September 1940.

Australia: “Beyond seven mountains”

and seven seas

The 250 German and 200 Italian survivors[88] „Nominal Roll of German Internees for Melbourne“, NAA_Item657104. of the sinking of the Arandora Star were not exclusively Nazis or fascists. They were taken off the Dunera in Melbourne on September 3, 1940. In order to fill camp capacities (or rather, not to exceed the capacities of the camps intended for the other 2,000 internees), they were taken together with 96 mostly Jewish refugees – among them Sigurd Lohde – to Camp 3 in the vicinity of Tatura (State of Victoria). At times, Nazi victims were housed there together with German and Australian Nazis and Italian fascists.

Everything in view? Tensions arose in camps in Tatura (here Camp 1, 1943).

Photo: C.T. Halmarick, Australian War Memorial No. 065008.

The Australian military ignored protests, and there were several incidents. With the closure of Camps 7 and 8 near Hay (New South Wales) in the spring of 1941 and the transfer of the approximately 1,900 Dunera internees locked up there to Tatura, opportunities arose to accommodate the 96 men in a non-threatening environment.

In the camps, the internees mobilized against inactivity and depression. They organized extensive activities for sports, education, and self-administration. These included performances by the many professional musicians and theater people. In Camp 7 Hay, plays were written that addressed the situation of imprisonment in an ambiguous and ironic way. This was revealed by show titles such as “Hay Fever” (literally also alluding to the place of detention) or songs such as “Say Hay for Happy.” At the end of 1940, “Snow White – S3828” premiered, in which “Doc” Kurt Sternberg[89] Kurt Sternberg (1899) worked as a film producer in Germany and in exile in Britain. took up motifs from Disney’s popular animated classic from 1937. In February 1941, he compiled elements from previous shows[90] Albrecht Dümling, The Vanished Musicians, Lausanne, 2016, p. 262. See Kurt Lewinski's diary in the Archive of Judaica, University of Sydney (Shelf List 17). under the title “Snow White and the Seven Hay Days.” The Snow White motif picked up on a commonality between the fairy tale character and the internees: all of them had been innocently driven from their homeland to a land “behind seven mountains.” The chorus of one song[91] Words by Hans Blau, music by Werner Baer (both Queen Mary Group), cited in Dümling aao, page 274. makes it clear that cultural activities were not an end in themselves:

“It‘s hope that keeps us going in our longing

For some happiness or luck.

So what if Destiny’s opposed – we see it

Coming back.”

Sigurd Lohde was housed in Camp Tatura 3 together with many musicians who had been deported from Singapore to Australia on the Dunera or the Queen Mary. There, too, people composed, sang, and performed theater. One example was the revue “Laugh and Forget” with numbers such as “How to Go to Bed” and a fashion show[92] Ibid, page 273.. It is not known whether and how Sigurd Lohde was involved in these productions.

By the spring of 1942, hundreds of internees had volunteered for British pioneer units or other war-related work and had been taken to England. After Pearl Harbor[93] Japan entered the war with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, accessed on August 25, 2025. and the Japanese attack on the northern Australian city of Darwin[94] Wikipedia on the air raids on Australia, accessed on 25 August 2025. on February 19, 1942, there was a shortage of labor in Australia due to increased conscription. As a result, many internees were deployed outside the camps to work in fruit harvesting, among other things. Accordingly, in April 1942, Lohde listed fruit picker[95] Military file of Sigurd Sigismund Lohde, NAA_ItemNumber6254965. as his current occupation.

In Australian uniform

The end of the internments can be dated to the spring of 1942. The internees who were still in Australia were called upon to enlist in the Australian Army. They were promised[96] Cf. Note from the Adjudant-General to the Australian Parliament, March 29, 1946. National Archives of Australia (NAA), NAA_ItemNumber4938132, sheet 28, paragraph d. a residence permit or naturalization Down Under.

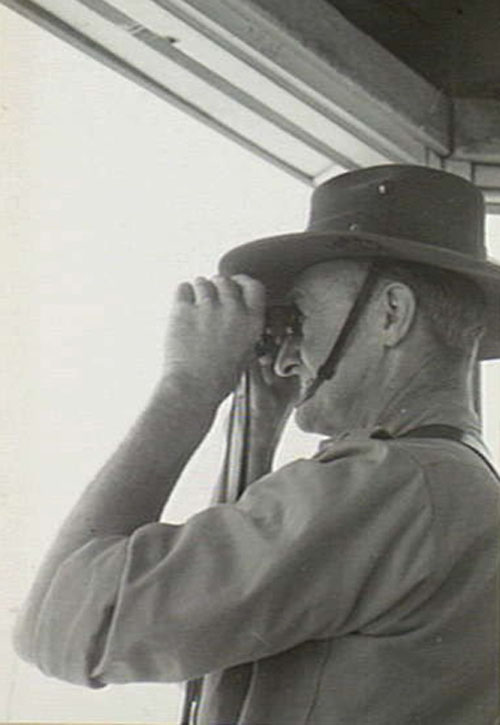

Like many of his companions (including Dehn, Wasser, Laufer, Schwarz, etc.), Sigurd Lohde also enlisted. On April 8, 1942, he began his service with the 8th Employment Company[97] Military file aao. (service number V377393). This unarmed unit consisted of up to 600 former internees[98] See War Diary of the 8th Emp Coy, Australian War Memorial AWM52 22/1/17., exclusively of German and Austrian origin. It was not only the largest company, but also the Allied unit with the highest number of Jewish soldiers. The former internees were proud to now be serving the common war effort, even though many would have preferred to fight the Nazis with weapons.

There was also a shortage of non-commissioned officers. Sigurd Lohde was promoted to corporal[99] Military files aao. after only one week of service. Military experience from World War I was not a general requirement (e.g., Franz Lebrecht) for this promotion, although Lohde had served in World War I. In October 1942, Lohde was promoted to acting sergeant and in September 1945 to sergeant. He was stationed in Tocumwal, among other places, where soldiers of the 8th were called upon to transfer between trains of different gauges at the border station between the states of New South Wales and Victoria.

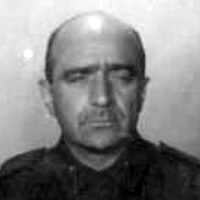

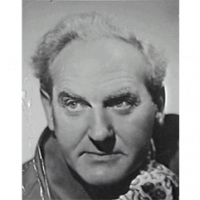

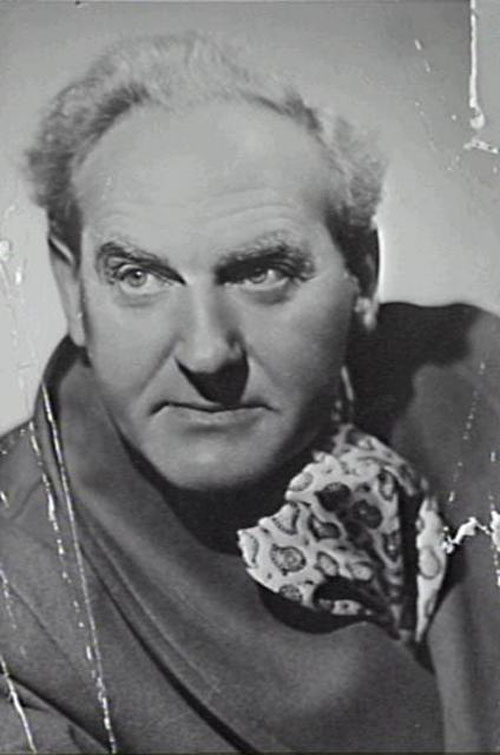

Sigurd Lohde in the uniform of the Australian Army. Photo: Lohde family archive.

Sgt. Sigurd Lohde (left) as Snow White’s lawyer.

Photos by Dunera Boy Harry Jay appeared in a major report in Pix Magazine in June 1943. Source: Trove Archive, Australia.

Where is Snow White?

The composition of the 8th Employment Company was also special in another sense, because many artists had joined the unit. Even in uniform and after often hard work, many used their leave passes to go to the theater. And they themselves enriched the cultural life at their stations with concerts[100] Dümling aao., page 283. Among other things, the soldiers benefited from the freedoms granted to them by their popular commander, Captain Edward Broughton[101] E.R. Broughton, biography by Dunera Boy Klaus Loewald in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed on 30.8.2025. (1884–1955). Due to the many cultural activities, the soldiers occasionally jokingly referred to their unit as the “Entertainment Company.”

In 1943, they took this to the extreme: “Doc” Kurt Sternberg rewrote and expanded parts of the “Snow White” program. The result was “Sgt. Snow White,” an anti-fascist musical with a Seven Dwarfs feel and numerous allusions to their experiences in internment and the army, as well as German-English puns.

The play made it to the stage of Melbourne’s Union Theatre with three performances starting on April 17, 1943—the anniversary of the transition from internment to the army. In addition to professionals and amateurs on and behind the stage, even Captain Broughton is said to have not shied away from a small cameo appearance[102] Inglis, Spark et al. „Dunera Lives. Profiles“, Melbourne 2020, page 13..

The linguistic arsenal included allusions, jokes, puns, and rewritten versions of popular songs. Because the performance was in English, the plates, knives, forks, etc. of Grimm’s dwarfs became “plate-chens, knife-chens, fork-chens,” etc. Or: The queen refers to dancers as “Jew-ropeans. Many of them from Austria. We call them Austri-Aliens.“ ”These witty formulations actually masked a more serious concern, since the racial persecution that lay behind the newly coined ‘Jew-ropeans’ persisted in Australia for some time as a defence against aliens“, explains Berlin music historian Albrecht Dümling[103] Dümling aao., page 299..

As befits a good show, the entire play and this scene ended with the wedding[104] Ibid, page 302. of the female title character, who had been absent throughout (because she had been expelled), to Prince Charming.

A poem written in London by Dunera boy Simon Hochberger, entitled “The European” or “Sounds of Europe[105] Ibid, page 305.,” ended with a call to resist the Nazis:

“The armies of freedom are on their way

Forward worker – Forward soldier

The hangmen of Europe will PAY!!!”

Cartoon of Sigurd Lohde by Fritz Schönbach in a report by the army magazine SALT[106] "They don't forget" in SALT Nr. 4, 26.4.1943. Entnommen aus Dunera News Nr. 5 (1985), Seite 13. about the 8th Employment Company.

”Sigurd Lohde recited this combative poem in a way that had a powerful effect on the audience,“ Dümling quoted from a review in ”The Listener In[107] Ibid, quoting Catherine Duncan „Snow White Joins The Army. Show as pointer to Theatrical Future” in The Listener In, Melbourne, 22.-28.5.1943.“ magazine. According to the review, ”it was one of the most impressive theatrical moments of the evening.“

Sgt. Sigurd Lohde wrote the lyrics and music for the “8 Aust Employment Coy March.” Courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Australia, inventory no. 4466.

Does anyone know anything about the whereabouts of the lost sheet music for the march? Please contact dunera.de.

This magazine looked beyond its radio horizon and highlighted the new interpretation of Grimm’s fairy tale, as the play was based on the personal experiences of the performers. This could open up new paths, the reviewer suggested, alluding to Australia’s theater scene under the title ”Novel Show as Pointer to Theatrical Future.”

The New York-based Jewish weekly magazine “Aufbau[108] Irma Schnierer, “Award-winning Europeans in Australia,” in Aufbau (New York), January 21, 1944, page 10.,“ reported on January 21, 1944, that author Simon Hochberger (Dunera) and composer Werner Baer (Queen Mary) had won an anonymous song contest for soldiers organized by the Australian broadcaster ABC with ”Sounds of Europe” and that the song had been broadcast nationwide. The judges were later surprised to have awarded the prize to foreigners, Dümling added. He smugly remarks that a printing of the winning poem[109] Dümling aao., page 306. was waived.

Australian „Pix“ Magazine headlined its richly illustrated story “Alien Soldier’s Show Twits Nazis” and decorated it with large photos by Dunera boy Harry Jay. The reviewer described the evening as “theater of flesh and blood” and “an eye-opener as to what can be done in a soldier show by imaginative and resourceful production, even with limited facilities and a mostly amateur cast.“ The author also mentioned Sigurd Lohde. A photo shows him as a lawyer whose stage name, “Dr. Blizzard of Oz,” alludes to both The Wizard of Oz and a snowstorm.

After receiving very positive reviews in the Australian press, the play was performed three more times in May 1943. New performances did not take place until decades later. In Sydney, students from the JMC Academy staged “Sgt. Snow White” again, exactly 81 years to the day after its premiere. This performance was directed by Ian Maxwell and Joseph Toltz.

Life and work in Sydney

While still serving in the army, Sigurd Lohde applied for a residence permit in 1944, stating his occupation as “chiropodist and masseur[110] Application for permit to enter Australia, dated 7.4.1944 in NAA_ItemNumber7843960.,” as he had done in other Australian documents. His naturalization was dated August 11, 1945; Sigurd Lohde was therefore an Australian citizen when he was discharged into civilian life on August 30, 1945. The army’s final medical examination[111] Ibid, discharge papers Sigurd Lohde. found him to be “unfit for heavy manual labor or long marches.” He was discharged to Sydney, 22 Roslyn Gardens, where his cousin Lotte Miller[112] Charlotte Miller arrived in Sydney on April 24, 1939, aboard the Orungal. (NAA_Item30420356; not digitized). lived.

In 1946, Lohde was listed in the electoral register[113] Voter list for Darlinghurst (Sydney) 1946, via ancestry. of the Sydney district of Darlinghurst and again as a chiropodist and masseur. He himself reported on the period after his military service: “I was a farmer, a domestic servant, a tie salesman, a department store clerk, a factory worker, and finally I opened a small milk bar[114] „Telegraf“ aao. in Sydney. That’s where everyone met.” He financed the milk bar with a lottery win[115] The family confirms corresponding reports. Emails from Kevin Lohde to dunera.de. of £1,000.

In the 1949 and 1954 electoral registers, Sigurd Lohde was now listed under his stage name Sydney Loder[116] See Glenmore voter list, 1946, via ancestry.de. and as an actor in the Sydney suburb of Glenmore, as he was naturally trying to gain a foothold in his chosen profession in Australia. He worked in radio and on stage, possibly under rather poor conditions, as he later reported. Among other places, he performed at the Palace Theatre and the Theatre Royal in Sydney.

Sydney Loder.

Courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

As a rebellious gold digger in Aussie cinema

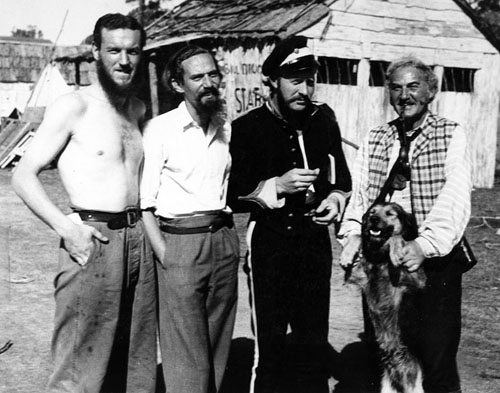

Break on the set of “Eureka Stockade”: Sigurd Lohde, now Sydney Loder (right), with colleagues.

Source: Wikimedia (public domain).

He adopted the anglicized stage name Sydney Loder in 1948 at the latest, when he landed a role in the film “Eureka Stockade[117] Wikipedia entry on the film “Eureka Stockade”, accessed on August 14, 2025..” The film by director Harry Watt dealt with the gold prospector uprising of 1854 in Ballarat (120 km west of Melbourne). Although British troops brutally suppressed the protest, Eureka Stockade is considered the birth of Australian democracy[118] Wikipedia on the Eureka Stockade, accessed on August 14, 2025. and the introduction of universal suffrage. Lohde played the leading role of the historically documented Hanoverian Frederick Vern[119] „Gold in Victoria. Frederick Vern“. Geman Australia online, accessed 15.8.2025., for whose capture the colonial authorities had offered a sensational £500 reward by the standards of the time.

The world premiere in London at the end of January 1949 was followed by the Australian premiere in early May. This period was marked by increasing social tensions Down Under. In mid-1948, the Queensland state government had likened a strike by 3,000 railway workers[120] Wikipedia on the railway strike of 1948, accessed on August 15, 2025. to a communist uprising[121] Vgl. Menzies on Coal Strikes Futility in The Argus from 5.4.1949 via Trove.. In New South Wales, 23,000 miners went on strike from the end of June 1949 until the government deployed the military as strike breakers[122] Wikipedia on the miners' strike of 1949, accessed on August 15, 2025. to force an end to the strike.

“The new conservative government headed by Robert Menzies[123] Australian film scholar Paul Byrnes in “Curator's notes” on “Eureka Stockade,” Australian Screen (Australian Film Archive NSFA), accessed on 20.8.2025. was less interested in promoting Australian film, or British films made by left-leaning directors like Harry Watt.” The press coverage focused, among other things, on the lead actor Chips Rafferty, who was characterized as miscast: “No one would have been inspired by Rafferty’s leadership to revolt against tyranny.” There was also a nationalistic-cynical note[124] No Epic“, Rezension in „The Advertiser“ (Adelaide) from 27.1.1949 via NLA-Trove.: “It is no disadvantage for Australia that the six leading actors behind Rafferty were ‘imported’ from England.”

Conservative reviewers used criticism of the film’s craftsmanship to obscure the political explosiveness of the story about the struggle for social justice and against exploitation by the state. “‘Eureka Stockade’ had become the wrong film at the wrong time, at least for some.” “Pix” Magazine chose the headline[125] “Pix" magazine on April 23, 1949, via Trove. “Attacked by critics, applauded by the public.”

Although there is no written evidence of Sydney Loder’s involvement in “Captain Thunderbolt,” a 1953 biopic about a legendary Australian outlaw, he can be clearly seen[126] Brief report on the restoration in the annual report 2023/24 of the Australian Film Archive NFSA (pages 22/23); information from Wikipedia and IMDB, accessed on 20 August 2025. in a trailer and in a photo from the digitization and restoration of this film.

An old love, a marsupial, and a boarding house in Berlin

The failure of the milk bar and his limited career prospects had prompted Sigurd Lohde to return to Germany. He arrived in West Berlin at the end of 1954 and initially lived at 34 Dallwitzstraße[127] Straschek Collection aao., West Berlin telephone directory, 1955, via Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin. in the Zehlendorf district. The entry in the telephone directory had the addition “actor and director.” From 1956, he shared a telephone number and address at Isoldestraße 2[128] West Berlin telephone directory, 1956, via ZLB. in Friedenau with Herta Plagemann.

Herta Elisabeth Plagemann[129] Berlin Registry Office, marriage entry no. 591 dated June 19, 1934, also documents the divorce by judgment dated February 5, 1941. Via ancestry. (née Neuendorf), was a childhood friend of Lohde’s, according to the tabloid BZ[130] “BZ” from May 15, 1956, in the Straschek Collection, aao. on the occasion of their wedding on May 15, 1956. A year earlier, “she suddenly heard his voice in a radio play. And the old love was rekindled.” The newspaper’s claim that Herta had previously been an operetta singer cannot be proven. In the civil registry entry for her first marriage in 1934, she is described as an office clerk[131] Civil registry entry no. 591 aao..

Telephone and address books show entries for Herta[132] West Berlin telephone directories via ZLB. prior to 1956 at Sanderstraße 6 and Isoldestraße 2 in Neukölln, both with the addition “restaurant”. The newspaper “BZ” joked that Lohde had become a partner in her restaurant through marriage.

Wedding photo of Sigurd Lohde and his childhood friend Herta. Source: Lohde family archive.

Herta Lohde ran a guesthouse called “Metropol,” as confirmed by entries in West Berlin telephone directories: “H Loder-Lohde” was listed with this business at Charlottenburg, Fasanenstrasse 71, at least between 1966 and 1969. After the sale in 1969, the “Metropol” could be found in a joint entry with another guesthouse at Kurfürstendamm 185 and its owner, Gerti Philipp. The last entry for the “Metropol[133] Yellow Pages West Berlin, 1973/74, via ZLB.” with Ms. Philipp is in the Yellow Pages of 1973/74.

Herta and Sigurd Lohde at the bar with Boomerang, Koala, and meatballs. Photo: Lohde family archive.

According to an Australian source[134] Pearl aao., page 195., Lohde ran a restaurant in West Berlin called “Das Kangeru”. The 1957 West Berlin telephone directory confirmed the existence of such a restaurant in the entry “Pearl aao., page 195.[135] West Berlin telephone directory, 1957, pages 405 and 407, via ZLB.”; the address given is Isoldestraße 2. Local historians consider it unlikely that “Zum Kängeruh” (or any restaurant for that matter) was located in this building: the curb in front of the building, which is still lowered today, and the facade design of the ground floor indicate that there used to be carriage houses or garages[136] Phone call with historian Joachim Perle. on the ground floor. Moreover, “Zum Kängeruh” probably did not exist for very long, as there are no further entries in the telephone directory or other evidence

Instead of the Lohdes, a Herta Dähn[137] Phone book 1958/59 via ZLB. A “Rügenklause” at the end of the 1960s at Uhlandstraße 43 is mentioned in “Berlin wie es schreibt und isst” (Berlin as it writes and eats), Munich, no date, page 178. is listed at Isoldestraße 2 in 1958/59 with the addition “Zur Rügenklause.” However, no later entries can be found for her either. Looking back, the Lohde family now assumes “that he redesigned the bar in Herta’s guesthouse[138] Emails from Kevin Lohde aao..”

On stage, in front of the camera and microphone

Sigurd Lohde was able to regain his footing as an actor[139] Straschek Collection aao.. His first engagement at the Renaissance Theater gave him support; among other things, he played in “Staats-Affairen” there in 1961; a recording was broadcast as a radio play. In the following years, he appeared at the Hebbel Theater (as the general director in „Mit den besten Empfehlungen“ / With Best Regards) and at the Theater Komödie, among others. He had temporary engagements in Essen and at the Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna, and from 1974 onwards he was on tour with the Grabowski Tour.

The radio play database[140] ARD radio play database aao. of the public broadcaster ARD links Sigurd Lohde with 90 radio plays. These include “Berlin – Alexanderplatz” by Hessischer Rundfunk, based on Alfred Döblin, and numerous productions by the former West Berlin pubcaster SFB. He played various roles in many episodes of “Damals war’s – Geschichten aus dem alten Berlin” (That’s How It Was – Stories from Old Berlin) by the German-language US station RIAS[141] Note: Numerous radio plays from the RIAS series are available on YouTube. His works range from adaptations of classics such as Shakespeare and Simenon to contemporary original material. A series based on C.S. Forester’s “Horatio Hornblower” books was intended for children, in which Lohde voiced El Supremo in several episodes.

For the GDR film distributor Progress, he worked on six cinema releases of films from France, Italy, and Czechoslovakia produced at the DEFA dubbing studio. Particularly noteworthy is the GDR co-production with France, “The Adventures of Till Ulenspiegel,” with Gerard Philipe in the rogue character invented by deCoster and as director. In GDR cinemas, the role of Grippeous, played by Raymond Souplex,[142] Links to S. Lohde in the movie database of the DEFA Foundation, accessed on August 25, 2025. could be heard with the voice of West Berliner Sigurd Lohde.

In front of the camera, he often distinguished himself in supporting roles. He was hired remarkably often by Artur Brauner’s Berlin-based CCC-Filmkunst[143] Film catalog of CCC-Filmkunst, search for Lohde, accessed August 20, 2025., including in 1963 as a postman in “Scotland Yard jagt Dr. Mabuse” (Scotland Yard Hunts Dr. Mabuse). For television, he appeared in Shakespeare adaptations such as “As You Like It” and “Much Ado About Nothing.” In around 20 years, in addition to his theater and radio work, he appeared in around 72 cinema and TV roles in front of the camera.

His last film was a mini-role as conductor in “Taxi nach Leipzig[144] Wikipedia on “Taxi nach Leipzig,” TV premiere on November 29, 1970. Accessed on August 15, 2025.” (Taxi to Leipzig). This TV crime drama, first broadcast in 1970, is significant for two reasons: Firstly, it dealt with an East-West plot: due to a murder case on the transit highway between the Federal Republic and West Berlin, the GDR authorities requested assistance from the West. Secondly, shortly before it was broadcast, the film was included by the pubcaster ARD as the first episode in their new crime series “Tatort,” (Crime Scene) which still exists today.

As a postman in the crime thriller “Scotland Yard hunts Dr. Mabuse” (1963). Courtesy of CCC-Film.

Family

The 1958/59 telephone directory listed Sigurd Lohde-Loder with the familiar telephone number, now at the neighboring house at Isoldestraße 3. From 1960 onwards, Sigurd and Herta lived in the Schmargendorf artists’ colony at Steinrückweg 3 – two doors away from Sigurd’s old apartment from 1934. In 1967, Sigurd and Herta moved to Dünkelbergsteig 1a[145] Last entry in the West Berlin telephone directory in 1978 via ZLB. in Zehlendorf.

According to the family, Sigurd Lohde treated Herta’s son from her first marriage, Lothar Plagemann[146] Emails from Kevin Lohde aao. (1935–2020), like his own child. Sigurd clearly inspired the young man, as he also chose to become an actor. Under the stage name Lothar Mann[147] Wikipedia and Synchronkartei on Lothar Plagemann (Mann), accessed on August 15, 2025., he appeared in various television films, as a voice actor, and on Berlin theater stages from 1960 onwards.

Autumn walk: Herta and Sigurd Lohde.

Photo: Lohde family archive.

Sigurd Lohde had already been able to contact the family of his brother Gerhard, who died in 1936, while Sigurd was still in Australia. Gerhard’s son Hans-Georg[148] Emails from Kevin Lohde aao. and Sigurd “developed a loving relationship.” Sigurd helped the family, who lived in Tangerhütte (GDR; now the state of Saxony-Anhalt), “primarily financially and materially, sending books, packages, and even washing machine parts,” and visited them often, according to the family.

“I didn’t find gold,” Lohde later joked, referring to the theme of his Australian movie. “But I made it through life and found my way back to Berlin,” the “Telegraf” newspaper quoted Sigurd Lohde[149] Telegraf aao. as saying a few months after his return from Australia.

Sigurd Lohde died on July 22, 1977, at his vacation home in Bad Sooden-Allendorf (Hesse). His widow Herta, who had taken on his stage name Loder, initially lived in the Berlin district of Wilmersdorf. In registration documents, she was later listed in Bavaria and Schleswig-Holstein as Herta Loder[150] Straschek Collection aao.. She died on April 25, 1997, her 75th birthday, in Berlin. She was buried alongside Sigurd at the Berlin Waldfriedhof Heerstraße cemetery.

The grave of Sigurd and Herta Lohde at the Waldfriedhof Heerstrasse Cemetery. Photo: Dehn.

Please note: We would like to express our sincere thanks to Kevin Lohde, a great grandson of Sigurd’s brother Gerhard Lohde. He and his parents provided us with extensive material. We would also like to thank Dr. Silvia Asmus and Katrin Kokot from the German Exile Archive 1933-1945 at the German National Library in Frankfurt/Main and Claudia Mayerhofer from the Theatermuseum in Vienna. Information about films and casts can be found primarily in the databases of IMDB (USA), the BFI (UK), the NSFA (Australia), Wikipedia, and the archives of the Berlin CCC-Filmkunst. The digital archives Zeitungsportal.de (German National Library) and Anno (Austrian National Library) were invaluable sources of information.

Footnotes

show

- [1]↑Weimar Registry Office. Birth record no. 278 dated June 12, 1899, via Ancestry.

- [2]↑Weimar Registry Office, marriage record no. 584 dated June 14, 1894, via Ancestry.

- [3]↑Weimar address book, 1899, via ancestry. Today: Puschkinstrasse 1. Wikipedia entry on the building, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [4]↑Wikipedia on Kaufstraße, now a cultural monument, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [5]↑Address books for Weimar, 1899 and 1906, via Ancestry.

- [6]↑Weimar City Archives, Files of the Building Authority, reference number II-8-284, Thuringia Archive Portal, accessed on September 20, 2025.

- [7]↑See Lernort Weimar. Traces of Jewish Life in Weimar and Jewish Places about the Israelite Religious Association Weimar, accessed on October 25, 2025. See Erika Müller, Harry Stein, Jewish Families in Weimar (Weimar City Museum, 1998).

- [8]↑Weimar Registry Office, death record no. 423 dated July 5, 1915, via ancestry.

- [9]↑Berlin telephone directory 1931/32 via ancestry.

- [10]↑See Lohde/Gork family tree via ancestry.

- [11]↑Birth and death dates of Sigurd Lohde's brothers via ancestry.

- [12]↑Stumbling stone for Gerhard Lohde in Tangerhütte (Saxony-Anhalt), Schillerstraße 4.

- [13]↑See Lohde/Gork family tree, op. cit.

- [14]↑Address and telephone directories for Vienna from 1938 to 1940, via ancestry.

- [15]↑Transport list from Theresienstadt via Arolsen Archives, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [16]↑Günter Peter Straschek. Collection of documents commissioned at Philipps University of Marburg for an unpublished encyclopedia of filmmakers in exile. The collection of material on Sigurd Lohde comprises 70 unnumbered sheets, mainly notes without evaluations or source references, as well as correspondence. Inventory EB 2012/153.D.01.2005 in the Exile Archive 1933-1945 of the German National Library in Frankfurt/Main, DNB entry. Wikipedia entry on Straschek, accessed on July 1, 2025.

- [17]↑Today: Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch. Lohde is not mentioned in a list of graduates.

- [18]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [19]↑Ibid. and Lohde's statements in his Australian military file, Australian National Archives NAA_ItemNumber6254965.

- [20]↑Wikipedia entry on Leopold Jessner, who was artistic director of the Schauspielhaus Berlin from 1919 to 1928, accessed on July 10, 2025.

- [21]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [22]↑“Arbeiterwille” Graz on August 28, 1928, page 4, via Anno (Austrian National Library).

- [23]↑Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, October 13, 1928, page 8, via Anno

- [24]↑Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, June 2, 1929, page 17, via Anno.

- [25]↑See also German Federal Archives, BArch R 56-III/1138.

- [26]↑„Kunst und Volk. Blätter der Breslauer Volksbühne e.V.“, no.1 1926/27“, page 31 via Deutsches Zeitungsportal.

- [27]↑1928 handbook of the German Stage Employees' Cooperative (GDBA), page 304, via ancestry.

- [28]↑Volksbühne am Rosa Luxemburg-Platz, Season Chronicle 1930 to 1940, accessed on August 20, 2025.

- [29]↑Berliner Börsen-Zeitung on November 18, 1924, page 41, via Deutsches Zeitungsportal.

- [30]↑ARD radio play database at the German Broadcasting Archive, accessed on August 25, 2025.

- [31]↑Grazer Tagblatt newspaper, January 5, 1929, page 11, via Anno.

- [32]↑GDBA Handbook 1931, page 304.

- [33]↑In “Der Schrei nach dem neuen Film” (The Cry for the New Film), Kinematograph, July 29, 1932, page 1, via Anno.

- [34]↑GDBA Handbook 1931, page 303 via ancestry, and autograph contact in “Mein Film” from issue 358, page 16, via Anno.

- [35]↑Berlin telephone directory, 1934, via Ancestry.

- [36]↑Wikipedia on the artists' colony, which was built in 1927 by the GDBA and the Schutzverband deutscher Schriftsteller (Protective Association of German Writers) to provide affordable housing for artists without social security, accessed on September 22, 2025.

- [37]↑“M” in the film database IMDB, accessed on 15 August 2025.

- [38]↑At that time, films were often shot in several languages simultaneously. Wikipedia entry on “Der Sprung ins Nichts” (The Leap into Nothingness), the German cinema market version of “Halfway to Heaven,” accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [39]↑Hallesche Nachrichten, December 24, 1931, page 17, via Deutsches Zeitungsportal.

- [40]↑Wikipedia on Paul von Hindenburg, one of the co-inventors of the “stab-in-the-back myth,” which claims that the homeland betrayed its successful military leaders during World War I. Retrieved on August 25, 2025.

- [41]↑Entry for the film “Theodor Körner” on IMDB, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [42]↑The “Deutsche Illustrierte” No. 41 from October 11, 1932, has no article accompanying its cover photo. On page 2, “The Path to the People's Community” is evoked in the text with photos of a paramilitary labor camp and a paean to the “real people's army” of the imperial era. Issue in the Dehn Archive.

- [43]↑“Kinematograph” from June 11, 1932, page 2, via Anno.

- [44]↑Wikipedia on the Reichsfilmkammer, accessed on August 16, 2025.

- [45]↑Cyril Pearl, “The Dunera Scandal,” Angus & Robertson, 1983, page 22, does not cite any sources.

- [46]↑Cinegraph and Wikipedia on “One Hundred Days,” accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [47]↑Wikipedia entry on actor Werner Krauß, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [48]↑“Neues Wiener Journal” on December 12, 1933, page 11 via ANNO.

- [49]↑Katharina Wessely, “Theater der Identität” (Theater of Identity). Radio Prague International on December 22, 2012, accessed on August 25, 2025.

- [50]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [51]↑“Mein Film,” issue 440 (end of May 1934), page 9, via Anno.

- [52]↑Kleine Volks-Zeitung, January 21, 1934, page 28, via Anno.

- [53]↑See Wikipedia entry on Tilla Durieux, accessed on August 28, 2025.

- [54]↑Wikipedia on the New German Theater, which existed in Prague from 1888 to 1938. Today, the building houses the Czech State Opera. Retrieved on August 25, 2025.

- [55]↑Vienna telephone directory, 1937, via Ancestry.

- [56]↑Wikipedia on Jewish director Hermann Kosterlitz, who made his career in Hollywood in the 1950s with comedies and the musical drama “One Hundred Men and a Girl.”

- [57]↑See Deutsche Synchronkartei (dubbiong database; list for Lohde is incomplete), accessed on September 20, 2025.

- [58]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [59]↑Wikipedia on the “Cross of Honor,” accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [60]↑Wikipedia on the “Anschluss” of Austria, accessed on August 20, 2025.

- [61]↑Wikipedia on the breakup of Czechoslovakia, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [62]↑Wikipedia on the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, accessed on September 25, 2025.

- [63]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [64]↑Home Office index card for Lohde, via ancestry.

- [65]↑Mark Piggott “A Beacon of Hope ...” University of London online, June 17, 2024, accessed August 15, 2025.

- [66]↑The Spectator on July 7, 1939, quoted in “A Light in Dark Times,” Exile Research Center, accessed on July 15, 2025.

- [67]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [68]↑Index card from the Home Office aao.

- [69]↑Australian personnel file for S. Lohde, NAA_ItemNumber9903925, via NAA.

- [70]↑“Neutral Port” in the IMDB film database, accessed on 15 August 2025.

- [71]↑“Convoy,” “Sailors Three,” and “Night Train to Munich” in the British Film Institute database, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [72]↑Headline in “Telegraf,” March 1, 1955, page 3, source: Lohde family archive

- [73]↑See Cyril Pearl aao.

- [74]↑According to numerous autobiographical accounts, the internees only learned of their destination, Australia, when the journey took too long, the climate became tropical, and the Dunera made its first stop in Freetown (Sierra Leone).

- [75]↑Wikipedia on the Battle of Dunkirk. The Dunera did not set sail until July 10, 1940.

- [76]↑See Sea Distances online, accessed on 25 August 2025.

- [77]↑The small town is located in the county of Surrey, south of London.

- [78]↑Around 1,000 internees from the British camp in Huyton were promised greater freedom and that their interned wives and children would follow shortly. Further migration, e.g. to the USA, was held out as a prospect. See Memorandum der Internierten von Camp 7.

- [79]↑Email from Alan Morgenroth to dunera.de dated August 14, 2025.

- [80]↑See list 7 of the 12 of 13 embarkation lists in the NAA archive, NAA_657104_Liste7_300, accessed on February 17, 2024.

- [81]↑The connection between List 7 and Lingfield is established by historians Alan Morgenroth and Rachel Pistol in “The Dunera Boys ... Who, when and why?” In “Dunera News” No. 109, page 10f.

- [82]↑Sigurd Lohde: “Lingfield Ballade,” bilingual original. Inventory number 4097 of the Jewish Museum of Australia.

- [83]↑Minutes of Question Time in the British House of Commons on July 9, 1940, accessed on August 20, 2023.

- [84]↑The decisions of the tribunals “at least reflected the opinion of the social class from which these King's Counsels (advisors to the king) came.” Several tribunals used inadequate guidelines to “exercise their anti-Bolshevik bias by declaring all veterans of the International Brigades who had fought fascism in Spain to be suspects.” This is the assessment of Canadian internee Eric Koch in “Deemed Suspect. A Wartime Blunder,” Toronto 1980, pages 9/10.

- [85]↑Wikipedia on Eleanor Rathbone, accessed on September 10, 2025.

- [86]↑Minutes of the House of Commons from July 10, 1940, accessed on September 10, 2025.

- [87]↑Francois Lafitte „The Internment of Aliens“ was the first book about Britain's treatment of the refugees. It was published in England in September 1940, so it could not take into account the events on the Dunera and in the camps.

- [88]↑„Nominal Roll of German Internees for Melbourne“, NAA_Item657104.

- [89]↑Kurt Sternberg (1899) worked as a film producer in Germany and in exile in Britain.

- [90]↑Albrecht Dümling, The Vanished Musicians, Lausanne, 2016, p. 262. See Kurt Lewinski's diary in the Archive of Judaica, University of Sydney (Shelf List 17).

- [91]↑Words by Hans Blau, music by Werner Baer (both Queen Mary Group), cited in Dümling aao, page 274.

- [92]↑Ibid, page 273.

- [93]↑Japan entered the war with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, accessed on August 25, 2025.

- [94]↑Wikipedia on the air raids on Australia, accessed on 25 August 2025.

- [95]↑Military file of Sigurd Sigismund Lohde, NAA_ItemNumber6254965.

- [96]↑Cf. Note from the Adjudant-General to the Australian Parliament, March 29, 1946. National Archives of Australia (NAA), NAA_ItemNumber4938132, sheet 28, paragraph d.

- [97]↑Military file aao.

- [98]↑See War Diary of the 8th Emp Coy, Australian War Memorial AWM52 22/1/17.

- [99]↑Military files aao.

- [100]↑Dümling aao., page 283

- [101]↑E.R. Broughton, biography by Dunera Boy Klaus Loewald in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed on 30.8.2025.

- [102]↑Inglis, Spark et al. „Dunera Lives. Profiles“, Melbourne 2020, page 13.

- [103]↑Dümling aao., page 299.

- [104]↑Ibid, page 302.

- [105]↑Ibid, page 305.

- [106]↑"They don't forget" in SALT Nr. 4, 26.4.1943. Entnommen aus Dunera News Nr. 5 (1985), Seite 13.

- [107]↑Ibid, quoting Catherine Duncan „Snow White Joins The Army. Show as pointer to Theatrical Future” in The Listener In, Melbourne, 22.-28.5.1943.

- [108]↑Irma Schnierer, “Award-winning Europeans in Australia,” in Aufbau (New York), January 21, 1944, page 10.

- [109]↑Dümling aao., page 306.

- [110]↑Application for permit to enter Australia, dated 7.4.1944 in NAA_ItemNumber7843960.

- [111]↑Ibid, discharge papers Sigurd Lohde.

- [112]↑Charlotte Miller arrived in Sydney on April 24, 1939, aboard the Orungal. (NAA_Item30420356; not digitized).

- [113]↑Voter list for Darlinghurst (Sydney) 1946, via ancestry.

- [114]↑„Telegraf“ aao.

- [115]↑The family confirms corresponding reports. Emails from Kevin Lohde to dunera.de.

- [116]↑See Glenmore voter list, 1946, via ancestry.de.

- [117]↑Wikipedia entry on the film “Eureka Stockade”, accessed on August 14, 2025.

- [118]↑Wikipedia on the Eureka Stockade, accessed on August 14, 2025.

- [119]↑„Gold in Victoria. Frederick Vern“. Geman Australia online, accessed 15.8.2025.

- [120]↑Wikipedia on the railway strike of 1948, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [121]↑Vgl. Menzies on Coal Strikes Futility in The Argus from 5.4.1949 via Trove.

- [122]↑Wikipedia on the miners' strike of 1949, accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [123]↑Australian film scholar Paul Byrnes in “Curator's notes” on “Eureka Stockade,” Australian Screen (Australian Film Archive NSFA), accessed on 20.8.2025.

- [124]↑No Epic“, Rezension in „The Advertiser“ (Adelaide) from 27.1.1949 via NLA-Trove.

- [125]↑“Pix" magazine on April 23, 1949, via Trove.

- [126]↑Brief report on the restoration in the annual report 2023/24 of the Australian Film Archive NFSA (pages 22/23); information from Wikipedia and IMDB, accessed on 20 August 2025.

- [127]↑Straschek Collection aao., West Berlin telephone directory, 1955, via Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin.

- [128]↑West Berlin telephone directory, 1956, via ZLB.

- [129]↑Berlin Registry Office, marriage entry no. 591 dated June 19, 1934, also documents the divorce by judgment dated February 5, 1941. Via ancestry.

- [130]↑“BZ” from May 15, 1956, in the Straschek Collection, aao.

- [131]↑Civil registry entry no. 591 aao.

- [132]↑West Berlin telephone directories via ZLB.

- [133]↑Yellow Pages West Berlin, 1973/74, via ZLB.

- [134]↑Pearl aao., page 195.

- [135]↑West Berlin telephone directory, 1957, pages 405 and 407, via ZLB.

- [136]↑Phone call with historian Joachim Perle.

- [137]↑Phone book 1958/59 via ZLB. A “Rügenklause” at the end of the 1960s at Uhlandstraße 43 is mentioned in “Berlin wie es schreibt und isst” (Berlin as it writes and eats), Munich, no date, page 178.

- [138]↑Emails from Kevin Lohde aao.

- [139]↑Straschek Collection aao.

- [140]↑ARD radio play database aao.

- [141]↑Note: Numerous radio plays from the RIAS series are available on YouTube.

- [142]↑Links to S. Lohde in the movie database of the DEFA Foundation, accessed on August 25, 2025.

- [143]↑Film catalog of CCC-Filmkunst, search for Lohde, accessed August 20, 2025.

- [144]↑Wikipedia on “Taxi nach Leipzig,” TV premiere on November 29, 1970. Accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [145]↑Last entry in the West Berlin telephone directory in 1978 via ZLB.

- [146]↑Emails from Kevin Lohde aao.

- [147]↑Wikipedia and Synchronkartei on Lothar Plagemann (Mann), accessed on August 15, 2025.

- [148]↑Emails from Kevin Lohde aao.

- [149]↑Telegraf aao.

- [150]↑Straschek Collection aao.