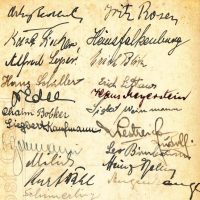

A caricature was found in Heinz Dehn’s estate. It was a gift on the occasion of his release from internment in March 1942 and a thank you for his work and commitment as a hut captain and in the camp administration. Ulrich Siegmund Laufer had drawn this caricature – so Heinz and Ulrich knew each other personally. Laufer had drawn several caricatures in the camps and his works seemed to be quite popular among the internees. Ulrich Siegmund Laufer and his comrade Max Schwarz died tragically in 1943. This article aims to keep the memory of the two young Dunera Boys alive, even though (and precisely because) little is known about them.

Paul Dehn, Peter Dehn, July 2025.

„Gone but not forgotten“

Ulrich Siegmund Laufer was born in Berlin-Schöneberg[1] Personal files U. Laufer, National Archives of Australia, NAA_ItemNumber9906530, retrieved Feb 18, 2025. on 11 May 1923 as the child of the Jewish neurologist Dr. Kurt Laufer[2] Worms registry office, marriage certificate no. 770 dated 23.12.1920, via ancestry.de. and his wife Friederika Ella née Bockmann[3] Worms registry office, birth certificate no. 1075 dated 9.11.1898 for Friederike Ella Bockmann via ancestry.de. There, in the Bavarian Quarter[4] Wkipedia (German) about the Bavarian Quarter, retrieved 20.3.2025., he spent the first years of his childhood.

Among the 16,000 Jewish residents of the quarter were the physicist Albert Einstein, the social democratic politicians Eduard Bernstein and Rudolf Breitscheid, the theater man Erwin Piscator, the publicist Hannah Arendt, the director Billy Wilder and the writer Inge Deutschkron. Literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki and photographer Gisèle Freund also grew up there. 6,000 Jews were deported from the district to extermination camps in 1943.

In 1927, the family moved to Neukölln, where Dr. Kurt Laufer ran a practice as a neurologist. From 1937, Carionweg 1 in the Halensee district of Wilmersdorf was the Laufers’ last known address in Berlin.

Ulrich had therefore spent his school years up to the age of 13 or 14 in the working-class district of Neukölln and then moved to a school in the more middle-class district of Halensee. Ulrich was still registered[5] Mapping the Lives, entry for Ulrich Laufer, rerrieved on 20.3.2025. in his parents’ apartment on May 17, 1939[6] Wikipedia (German) on the census of 17.5.1939 and the resulting Jewish register, retrieved on 10.2.2025..

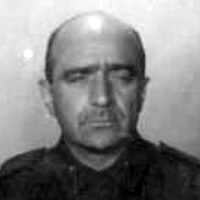

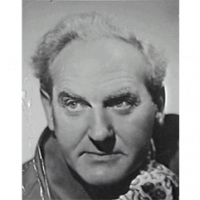

The only known portrait photo comes from Ulrich’s Australian army file.

With the Kindertransport to freedom

His youth suggests that Kurt and Ella were able to place their 16-year-old son Ulrich in one of the Kindertransports[7] Wikipedia (German) about Kindertransports, retrieved on 23.1.2025.. After the pogroms of November 1938, British special visas saved around 10,000 Jewish children and young people from Nazi persecution until the start of the war. The Jewish community had to pay 50 pounds for each child. However, no evidence of his participation in one of the Kindertransports has yet been found. No matter what support Ulrich received, he was able to leave the Nazi Reich: Although he had to leave his parents and friends behind in Berlin, the exile may have been something of a relief.

Ulrich had already registered for a US visa at the Berlin consulate in September 1938, which was approved with the number 45900. He presented himself[8] Personal files Ulrich Laufer, Archives of World Jewish Relief (AJR); email of 23.5.2025 by request of dunera.de. again in London on May 9, 1940. His destination was apparently New York, where his aunt Elisabeth Rosenthal had settled with her husband.

As an art student in London

Ulrich arrived in England on June 6, 1939[9] Ibid.. He lived at 37 Wood Lane, Highgate N6, subletting from Mrs. Pomford[10] Ulrich Laufer, Karteikarte des Home Office, via ancestry.de. Und Personalbogen AJR-Archiv, aao.. In Australia he named Mr. A.H. Parker[11] A.H. Parker, schoolmaster, and wife Bertha accdording to census of 29.9.1939, via ancestry.de. at 64 Talbot Road in the same district[12] Cf. family tree Parker/Ashby via ancestry.de. as his next of kin. Altham Hampton Parker[13] In Australia Laufer stated house number 67; 64 is correct. Cf. personal sheet U. Laufer NAA_ItemNumber8617711, routing slip of the AJR archive aao., entries for the Parkers in electoral rolls via ancestry.de. (22.2.1902 – 20.9.1976), a schoolmaster by profession, lived there with his mother Bertha Leonora (1864-1953). He was a German teacher at Highgate School and a follower of anthroposophy, founded by the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Parker’s niece Sheena Ashby[14] Sheena Ashby, niece of A.H. Parker; email to dunera.de of 24.5.2025. suspects that his friend and later wife, the potter Cicely Ashby, may have made the acquaintance. This acquaintance may have helped both of them to deepen their knowledge of the other’s language.

Ulrich was able to enrol at the Hornsey School of Arts and Crafts[15] The Hornsey College of Arts and Crafts existed from 1882 to 1996, Short info and Wikipedia, retrieved on 25.5.2025. in north London, where fine art, advertising design and applied industrial design[16] AJR, personal files loc.cit. were taught at the time. There is no known connection between the Parkers and the school. In Australia, he gave “commercial art[17] Internment files Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber9906530, NAA_ItemNumber8617711.” as a subject of his studies. One document mentions “IYR commercial art[18] Mobilization Attestation Form Ulrich Laufer, 26.5.1943, page 1; NAA_ItemNumber6232606.”. This is possibly an “in year retrieval”. Such programs are used – at least nowadays – in British universities to enable students to reclassify[19] Cf. University of South Wales, retrieved on 15.1.2025. their work if their grades are poor or insufficient. He was unable to obtain a degree after just one year of study.

Detention and internment

The policy of fighting against an alleged “5th column”, to which Churchill’s government insultingly included Jewish and political refugees as well as British citizens with roots in “enemy states”, did not stop at young refugees. Ulrich Laufer was arrested[20] Cf. NAA personnel sheet, loc.cit. and docket U. Laufer, loc.cit. in London on June 28, 1940 and taken to the camp in Kempton Park.

According to the minutes of the House of Commons, there was “not a single bed, not even a straw bag or chair, so that the sick and elderly internees had to sleep on the bare floor”. Secretary of State for War Anthony Eden[21] House of Commons, debate on internemnt on 20.8.1940, retrieved on 14.11.2024. blamed this on “the circumstances”. But who was responsible for “the circumstances”?

Reports of harassment and theft by the guards came not only from the horror journey of the Dunera, but also from British camps. In Kempton, internees “lost” watches and cash to corrupt guards[22] Simon Parkin „I remember the feeling of insult: When Britain imprisoned its wartime refugees“. The Guardian on 1.2.2022, retrieved on 15.1.2025.. Major James Braybrook, commander of Kempton Park Internment Camp, was later sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for “larceny, embezzlement and fraudulent conversion[23] The National Archives Kew, „Major James Braybrook, Commandant ….“ (catalogue entry), retrieved on 15.1.2025.”.

Kurt and Ella married on December 23, 1920 in Worms.

The fate of the parents Kurt and Ella Laufer

Ulrich’s father Kurt Laufer was born in Berlin on August 18, 1894. His parents – Ulrich’s grand parents[24] Birth entry Kurt Laufer, registry office Berlin no. 1995 from 23.8.1894, via ancestry.de – were Eugen Isidor and Elise Laufer, née Breslauer. The family lived in the Hansa quarter[25] Wikipedia (German) about Berlin-Hansaviertel, abgerufen am 27.11.2024., founded in 1874, at Flensburger Straße 9 in Berlin-Moabit. Kurt studied medicine in Heidelberg and passed his Physicum[26] Mapping the Lives über Kurt Laufer, retrieved on 11.12.2024. (intermediate examination) in Berlin . Kurt’s wife Ella Bockmann[27] Background information (German) about the Bockmann family on Die Wormser Juden 1933-1945, retrived 23.1.2025. was born in Worms on November 3, 1898. Her parents were the merchant Siegmund Bockmann and his wife Johanna, née Scharff. They also had a daughter, Elisabeth (Lizzi).

Kurt and Ella had married in Worms on December 23, 1920 and then moved to Berlin. The family lived at Luitpoldstrasse 28[28] Adressbücher von Berlin 1923 bis 1927, Digitale Landesbibliothek Berlin. from 1923. In 1927 they added the practice address at Bergstrasse 163[29] Berlin business directory 1927, loc.cit.. (today: Karl-Marx-Strasse) in Neukölln and the family moved to nearby Lahnstrasse 68[30] Berlin business directory 1935, loc.cit. in 1928. The Laufers’ last Berlin address was Carionweg 1[31] Mapping the Lives über Ella Laufer, loc.cit. in Berlin Halensee from 1937.

Kurt’s approbation[32] Wikipedia (German) about medicine in Jewish culture, retrieved on 2.5.2025. The article names Jewish physicians of international standing, including Nobel Prize winners. was revoked by the “Fourth Ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Act” on September 30, 1938, and with it his livelihood. This professional ban affected the 3,152 Jewish doctors[33] Thomas Gerst, „Vor 80 Jahren: Ausschluss jüdischer Ärzte aus der Kassenpraxis” (80 years ago: Exclusion of Jewish doctors from panel practice), Deutsches Ärzteblatt 16/2013, retrieved on 2.5.2025. who had been tolerated by the Nazis until then.

His Neukölln practice address was therefore no longer listed in the address directory of 1939[34] Berlin directory 1939, loc.cit.. After the November pogroms, he was arrested on November 14, 1938 as one of 30,000 “Aktionsjuden” and held in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp with the prisoner number 7838[35] Mail der Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen an Dunera.de vom 13.4.2025. until December 14, 1938.

Relocation and work in Bendorf-Sayn

Fritz and Paul Jacoby fled to Uruguay in mid-1940. From the end of 1940, mentally ill Jews may only be admitted to the Heil- und Pflegeanstalt in Bendorf-Sayn[36] Ministry of Interior, Circular of 12.12.1940, Cf Wikipedia über (German) about the Jacoby’sche Heil- und Pflegeanstalt, retrived on 15.12.2024., district of Koblenz (sanatorium and nursing home) run by the Reichsverein der Juden, which the Jacobys had managed.

Dr. Wilhelm Rosenau, appointed by the Jacobys as his successor, brought his specialist colleague Kurt Laufer and his wife Ella[37] Pete Vanlaw, „Bendorf-Sayn and My Cousin – An Update“, 15.1.2015; abgerufen am 16.5.2025. to the institution as nurses. This made Kurt Laufer one of the few Jewish “medical practitioners” who were allowed to treat only Jews[38] Thomas Gerst, loc.cit. from 1938 onwards.

From March 1942, there were signs that this medical facility was coming to an end. On June 15, 1942[39] Cf. Mapping the Lives über Ella und Kurt Laufer loc.cit., Lieselotte Sauer-Kaulbach „Der Autor Jacob van Hoddis: Patient in Sayn, Opfer des NS-Wahns“. In Rhein-Zeitung from 28.9.2021, retrieved on 12.11.2024., 331 men and women alone – including Ella and Kurt Laufer – were sent from Koblenz via Cologne and Düsseldorf to their deaths in the Sobibor extermination camp. Patients and staff – more than 580 people – were taken to extermination camps[40] Dietrich Schabow, „Juden in Bendorf 1199-1942. Eine Ausstellung zum Gedenken der Deportationen aus Bendorf im Jahre 1942“ (Jews in Bendorf. An exhibition to commemorate the deportations from Bendorf in 1942). In: Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte in Rheinland-Pfalz. 3. Jahrgang. Ausgabe 2/1993, Heft Nr. 5. Seiten 46-47. on a total of five transports. The Reich Ministry of the Interior ordered the closure[41] Ministry of Interior, circular from 10.11.1942, loc.cit. of the facility on November 10, 1942.

Other relatives

In 1869, the merchant Meyer (Meier) Jacoby founded the Israelitische Heil- und Pflegeanstalt für Nerven- und Gemüthskranke Sayn[42] Dietrich Schabow, „Juden in Bendorf 1199-1942 …“ loc.cit. near Coblenz for the adequate treatment and care[43] Milena Bagic, „Israelitische Krankenanstalt in Bendorf-Sayn, Asyl für Nerven- und Gemütskranke, Jacoby’sche Heil- und Pflegeanstalt“, Universität Koblenz-Landau, 2015, retrieved on 26.01.2025. of Jewish patients, taking their faith into account.a small clinic soon became a place known throughout Europe.

Advertisement for the clinic in the “Israelit”, February 11, 1884.

The number of patients rose from 112 (1888) to 174 (1905). Therefore, new buildings[44] „Sayn - Jüdische Geschichte / Jacoby'sche Anstalten“ (Sayn - Jewish History), retrieved on26.01.2025. became necessary. After the founder’s grandchildren fled, the Reich Association of Jews took over the clinic. The new director, Dr. Wilhelm Rosenau, escaped deportation because he lived in a “privileged mixed marriage”. He survived the war as a stoker on the clinic property, which was now administered by the city of Koblenz. The current owner is the Catholic group of companies Josefs-Gesellschaft[45] Yearly reports of Josefs-Gesellschaft, retrieved on 8.12.2024., which operates hospitals, facilities for the disabled, etc.

Ulrich Laufer had named his aunt Elisabeth as his next of kin on Australian forms. Her family had managed to flee to the USA: With her husband Max Rosenthal (he was best man at Ella and Kurt’s wedding), Elisabeth’s mother Johanna Bockmann and their 19-year-old daughter Gerti[46] US census 1950, via ancestry.de., they reached New York on October 3, 1940. The journey had taken them from their last place of residence in Milan via Naples and Lisbon[47] Passenger list of Nea Hellas from 3.10.1940, Application for naturalization in the USA from 27.5.1941, via ancestry.de. from August 26, 1940. Max practiced as a lawyer there in 1950, Elisabeth was a secretary[48] US census 1950 loc.cit. in an export company; their daughter Gerti no longer appeared as a member of the household.

Ulrich’s friend: Max Schwarz

The only known photo of Max is also the picture for his army ID card.

Max Schwarz[49] Australian Jewish Historical Society, biography Max Schwarz (not: Schwartz), retrieved on 5.12.2024. was born in Vienna on September 6, 1917. His parents were the railroad official Marcus Schwarz (*1882) and his wife Cilly (*1890), née Krumholz. Both came from Buczacz (Ukraine). Max’s brother Julius[50] Questionnaire Max Schwarz (Fürsorge-Zentrale der Kultusgemeinde Wien) from 23.5.1938 via ancestry.de. was also born there in 1912. Max graduated from the Elisabeth-Gymnasium in Vienna’s 5th district in 1936 and began studying medicine[51] Cf. .entry Max Schwarz in „Gedenkbuch für die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus an der Uni Wien 1938“ (Memory book for Nazi vicgims at Uni Vienna) including parts of his proff of study, retrieved on 08.12.2024. at Vienna University in the winter semester of 1936/1937.

After the “Anschluss[52] Wikipedia (German) about the „Anschluss“, retrieved on 20.4.2025.” of Austria to the Nazi Reich on March 12, 1938[iv], the Nazis fired more than 2,700 members of the university, most of them Jews. This also happened to Max after his third semester. Like most of them, Max decided to emigrate. Fellow sufferers included the older medical student Peter Huppert and the chemist Friedrich Eirich. They were among those who managed to escape to England. All three were deported from there on the HMT Dunera to Australia.

In the questionnaire for the Jewish emigration department, he named New York, North and South America or Palestine as possible destinations. His uncle Max Schwarz[53] Questionnaire loc.cit. and cousins from his mother’s side of the family were already living in New York.

Of the 9,180 students in the winter semester of 1937/38, 3,855 had to leave the University of Vienna; 2,230 of them were Jewish. Like Max, many managed to escape. But 90 of them were murdered in the Shoah[54] Universität Wien, „Vertreibung von Lehrenden und Studierenden 1938“ (Expulsion of teachers and students in 1938), retrieved on 10.5.2025..

Escape to England

Max Schwarz’s first station in exile was Kitchener Camp[55] Kitchener Camp. Refugees in Britain in 1939, registry. Retrieved on 17.5.2024. on the British Channel coast, where he worked in the kitchen. He was registered in Kingston (Surrey) on the occasion of the census in September 1939. He was arrested there on June 25, 1940. Two weeks later, he was deported to Australia on the Dunera. In Australia, he first named his father Marcus in Vienna as his contact person, and then his brother Julius in Damascus (Syria). Julius[56] Questionnaire loc.cit. later went to the USA. Max’s father Marcus Schwarz was deported by the Nazis to the Opole ghetto on February 15, 1941 and died in 1942. Only 28 of the 2,003 Jews from Vienna who were deported there survived the liberation. Nothing is known about the fate of his mother Cilly.

Ulrich and Max: Deportations overseas

Victims of the Churchill government’s xenophobic policies included around 10,000 men who were deported overseas on five overcrowded ships between June 24 and July 10, 1940. They were mostly German and Austrian refugees, but also a small number of prisoners of war, civilian internees, businessmen and members of the merchant navy of the enemy states, as well as Britons of Italian descent, who Britain got rid of by deporting them to Canada and Australia. Tens of thousands of people, including women and children, were put behind bars in England, including in camps on the Isle of Man. Churchill treated the natural allies of the Allies like criminals.

Almost 800 men died on July 2, 1940 when the Arandora Star, the second internment ship, was sunk. Around 450 survivors, including German Nazis and Italian Fascists, were sent on a voyage from Liverpool on July 10, 1940 on the HMT Dunera, along with 2,000 Jews and Nazi opponents. Only after many days on board and in tropical waters did they realize that their destination was not – as many were promised – Canada, but Australia. After 57 days of horror, during which the internees were harassed and systematicly robbed by guards, the ship arrived in Sydney.

Behind barbed wire in Australia

Ulrich Laufer drew this caricature of Heinz Dehn’s activities as hat captain and in the camp council in 1941 on the occasion of the transfer of internees from Hay to Tatura. Source: Dehn family archive.

Around 2,000 men were transported from the port area to two camps near the railroad terminus at Hay in the state of New South Wales. Ulrich Laufer was sent to Camp 8[57] “Report on Internee“ Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber9906530.. It is not known when he and Max Schwarz met and became friends. Max was placed in Compound II of Camp 7 near Hay (Hut 24)[58] “Report on Internee“ Max Schwarz, NAA_ItemNumber9907139. And List of internees of Camp 7 Hay Compound II, who refused to have their names passed on to the Red Cross. In NAA_ItemNumber390299, page 26f.. These camps were evacuated in mid-1941 and the internees were transferred to Camp Tatura 2. If Ulrich and Max had not already met on the Dunera, they may have met again in Tatura.

Ulrich’s British file card states “to be released[59] Ulrich Laufer, files of Home Office. in Australia … 25.1.1941″. The fact that this release was not carried out in 1941 may have been due to Australia’s policy of preventing the release of internees on its territory. On the other hand, traveling by ship during the war was dangerous.

Everyday scene in the internment camp – caricatured by Ulrich Laufer.

Ulrich Laufer (kneeling) and his comrades of hut 6.

Source: Victorian Collection, public domain.

Life in all the camps was bordered by three rows of barbed wire. The internees kept up their courage and will to live. They organized sports teams, music and theater performances. The camp university also taught the basics of artistic activity. It can be speculated that Ulrich Laufer used this to deepen his artistic skills – perhaps in the direction of caricature. The sheet on which Ulrich Laufer caricatures Heinz Dehn’s work on the camp council is a practical expression of this. A card for Erich Tichauer, a group portrait and the Christmas card, on which Laufer depicts an internee with a mosquito net watering a flower bed, also have ironic features. The staff of Barrack 6 in Camp Tatura 2 were also “victims” of his drawing pencil; he also immortalized himself in the picture – drawing the group.

Card for Erich Tichauer, who directed the Jewish choir at Camp Tatura 2.

Dear reader, only a few works by Ulrich Laufer are known to us. We look forward to receiving any information about other works and your e-mail.

By the spring of 1942, at least half of the German and Austrian refugees took the opportunity to enlist in the British engineer troops or to support the Allies in England in other ways. The dissolution of the camps near Tatura from the spring of 1942 was linked to the desire of most of the internees remaining there to settle in Australia. This had long been refused by racist governments. Internees were only accepted when conscription into the army in the spring of 1942 created a high demand for labor. As a result, a later right of residence or citizenship was linked to the more or less voluntary obligation[60] Cf. Minute of the General-Adjudant to Australian Parliarment from 29.3.1946. NAA_ItemNumber4938132, page 28, point d. to join the Australian army. However, Ulrich Laufer and his friend Max Schwarz did not decide to take this step until much later. They were therefore only released from internment in May 1943.

Labor soldiers in Australian uniform

The German and Austrian internees, including Laufer and Schwarz, were grouped together in the 8th Australian Employment Company[61] The unit existed from April 1942 to January 1946 . War diary of th 8th Australian Employment Company, Australian War Memorial, AWM52-22-1-17, parts 1 to 10.. One of the main tasks of this unarmed work unit was loading work in the port of Melbourne and the reloading of weapons, ammunition and other goods between trains of different gauges[62] The Australian states had not agreed on a common track gauge. It was not until 2009 that the broad gauge track was abandoned from the Albury (state of New South Wales) to Seymour (Victoria). See Wikipedia on rail gauges in Australia, retrieved on 20.4.2025. in the border area of the states of New South Wales and Victoria. “We are defending the 70th defense line”, Franz Lebrecht had commented ironically; like many of his comrades the Queen Mary internee would have preferred to face the Nazis with a gun, like many interned anti-Fascists.

Kurt Wittenberg created an emblem for the 8th Employment Company.

A freight train stops in Tocumwal. The station lost its role when a uniform track gauge was introduced. Photo: Dehn.

Ulrich (V510654) und Max (V510653), who had been given consecutive service numbers, were posted to Tocumwal station[63] The standardization of the track gauge in New South Wales and Victoria significantly reduced the role of the reloading stations and former operating locations of Tocumwal and Albury. Today there is only one track in Tocumwal. The station building houses a railroad museum and is a listed building. (New South Wales). The station [photo station today] is only a short distance from the Murray River, which forms the southern border of the town and the state. The other bank lies on the territory of Victoria. At the time, the river offered one of the few recreational opportunities for the soldiers. However, swimming was not without danger. Ulrich Laufer and Max Schwarz sought to cool off by swimming in Australia’s hot summer. They drowned in the Murray River on the afternoon of December 30, 1943.

Death in Murray River

The Australian army set up a court martial[64] The medical military file of Max Schwarz (erroneously Schwartz) contains the investigation files of the court martial, also concerning Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber31554061. to determine the cause of death. Schwarz had called for help, reported the soldier Kurt Süsskind. Both comrades had been carried downstream by the current and then drowned. He had tried in vain to get help quickly. The soldier Hans Hirschberg heard the cries for help, borrowed a boat and searched in vain for his comrades in the current.

When the company commander, Major Broughton, heard about the incident, he sent a search party to the shore, which remained active until nightfall. The search continued over the next two days. On the morning of January 1, he learned that the body of Ulrich Laufer had been found, Broughton testified. A little later he received the news that the body of Max Schwarz had been seen about 5 miles away.

Ulrich Siegmund Laufer was buried “with military honors[65] War diary loc.cit., vol. 8 page 2.” at the Tocumwal cemetery on the evening of January 1, 1944 at around 7:30 pm.

He himself and a group of soldiers had recovered the body of Max Schwarz, Major Broughton stated. Corresponding entries are made in the unit’s war diary[66] Ibid, vol. 7, page 96. on December 30 and 31, 1943.

The leave passes are archived in the file of the military court.

Ulrich Laufer and Max Schwarz were buried next to each other in the Tocumwal cemetery.

Max Schwarz was buried there next to Ulrich Laufer[67] Ibid. on January 2. This was carved on his gravestone: “May your soul rest in peace. Gone but not forgotten.”

The coroner found that both had died from drowning due to a lack of oxygen. It was an accident[68] Court martial in army files Schwarz loc.cit., page 10. that had occurred “independently of the conditions of service”, the military court concluded the investigation.

In the order of the day on January 6, Captain Broughton prohibited bathing in the Murray River except under the supervision of competent persons or specially appointed military personnel.bathing in the Murray River[69] War diary loc.cit..

The only dead PTE’s of the 8th Australian Employment Company are commemorated today by an entry on the Roll of Honor of the Fallen Australian Soldiers at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra (photo Dehn).

The commander of the 8th Employment Company was Captain Edward “Tip” Broughton[70] A detailed biography of the popular officer was published by Dunera Boy Klaus Loewald in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, retrieved on 5.5.2025.. The half-Maori was very committed to his soldiers and became a father figure, especially for the younger ones. Dunera Boy and army comrade Walter Pollak, who, like Max Schwarz, came from Vienna, recalled a later conversation[71] Walter Pollak „Captain E.R.M. Broughton“ in Dunera News no. 24 (June 1992), page 7, retrieved on 16.11.2024. with the officer about the death of the two comrades:

“This accident affected me more than I can tell you. Two young men who went through the trauma of beeing torn from their families as youngsters, shipped off to a strange country, interned for 2 1/2 years and finally, before getting to know the beauty of life, ended up as 2 bloated corpses on the river banks.” NL24 page 7.

Edward Renata (Tip) Muhunga Broughton (1884 –1955). Photo: Harry Jay.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Sarah from the volunteer team who handles archive requests at World Jewish Relief and A.H. Parker’s niece Sheena Ashby. Both supported the research on Ulrich Laufer’s short time in Britain with valuable information and documents.

Footnotes

show

- [1]↑Personal files U. Laufer, National Archives of Australia, NAA_ItemNumber9906530, retrieved Feb 18, 2025.

- [2]↑Worms registry office, marriage certificate no. 770 dated 23.12.1920, via ancestry.de.

- [3]↑Worms registry office, birth certificate no. 1075 dated 9.11.1898 for Friederike Ella Bockmann via ancestry.de

- [4]↑Wkipedia (German) about the Bavarian Quarter, retrieved 20.3.2025.

- [5]↑Mapping the Lives, entry for Ulrich Laufer, rerrieved on 20.3.2025.

- [6]↑Wikipedia (German) on the census of 17.5.1939 and the resulting Jewish register, retrieved on 10.2.2025.

- [7]↑Wikipedia (German) about Kindertransports, retrieved on 23.1.2025.

- [8]↑Personal files Ulrich Laufer, Archives of World Jewish Relief (AJR); email of 23.5.2025 by request of dunera.de.

- [9]↑Ibid.

- [10]↑Ulrich Laufer, Karteikarte des Home Office, via ancestry.de. Und Personalbogen AJR-Archiv, aao.

- [11]↑A.H. Parker, schoolmaster, and wife Bertha accdording to census of 29.9.1939, via ancestry.de.

- [12]↑Cf. family tree Parker/Ashby via ancestry.de.

- [13]↑In Australia Laufer stated house number 67; 64 is correct. Cf. personal sheet U. Laufer NAA_ItemNumber8617711, routing slip of the AJR archive aao., entries for the Parkers in electoral rolls via ancestry.de.

- [14]↑Sheena Ashby, niece of A.H. Parker; email to dunera.de of 24.5.2025.

- [15]↑The Hornsey College of Arts and Crafts existed from 1882 to 1996, Short info and Wikipedia, retrieved on 25.5.2025.

- [16]↑AJR, personal files loc.cit.

- [17]↑Internment files Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber9906530, NAA_ItemNumber8617711.

- [18]↑Mobilization Attestation Form Ulrich Laufer, 26.5.1943, page 1; NAA_ItemNumber6232606.

- [19]↑Cf. University of South Wales, retrieved on 15.1.2025.

- [20]↑Cf. NAA personnel sheet, loc.cit. and docket U. Laufer, loc.cit.

- [21]↑House of Commons, debate on internemnt on 20.8.1940, retrieved on 14.11.2024.

- [22]↑Simon Parkin „I remember the feeling of insult: When Britain imprisoned its wartime refugees“. The Guardian on 1.2.2022, retrieved on 15.1.2025.

- [23]↑The National Archives Kew, „Major James Braybrook, Commandant ….“ (catalogue entry), retrieved on 15.1.2025.

- [24]↑Birth entry Kurt Laufer, registry office Berlin no. 1995 from 23.8.1894, via ancestry.de

- [25]↑Wikipedia (German) about Berlin-Hansaviertel, abgerufen am 27.11.2024.

- [26]↑Mapping the Lives über Kurt Laufer, retrieved on 11.12.2024.

- [27]↑Background information (German) about the Bockmann family on Die Wormser Juden 1933-1945, retrived 23.1.2025.

- [28]↑Adressbücher von Berlin 1923 bis 1927, Digitale Landesbibliothek Berlin.

- [29]↑Berlin business directory 1927, loc.cit..

- [30]↑Berlin business directory 1935, loc.cit.

- [31]↑Mapping the Lives über Ella Laufer, loc.cit.

- [32]↑Wikipedia (German) about medicine in Jewish culture, retrieved on 2.5.2025. The article names Jewish physicians of international standing, including Nobel Prize winners.

- [33]↑Thomas Gerst, „Vor 80 Jahren: Ausschluss jüdischer Ärzte aus der Kassenpraxis” (80 years ago: Exclusion of Jewish doctors from panel practice), Deutsches Ärzteblatt 16/2013, retrieved on 2.5.2025.

- [34]↑Berlin directory 1939, loc.cit.

- [35]↑Mail der Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen an Dunera.de vom 13.4.2025.

- [36]↑Ministry of Interior, Circular of 12.12.1940, Cf Wikipedia über (German) about the Jacoby’sche Heil- und Pflegeanstalt, retrived on 15.12.2024.

- [37]↑Pete Vanlaw, „Bendorf-Sayn and My Cousin – An Update“, 15.1.2015; abgerufen am 16.5.2025.

- [38]↑Thomas Gerst, loc.cit.

- [39]↑Cf. Mapping the Lives über Ella und Kurt Laufer loc.cit., Lieselotte Sauer-Kaulbach „Der Autor Jacob van Hoddis: Patient in Sayn, Opfer des NS-Wahns“. In Rhein-Zeitung from 28.9.2021, retrieved on 12.11.2024.

- [40]↑Dietrich Schabow, „Juden in Bendorf 1199-1942. Eine Ausstellung zum Gedenken der Deportationen aus Bendorf im Jahre 1942“ (Jews in Bendorf. An exhibition to commemorate the deportations from Bendorf in 1942). In: Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte in Rheinland-Pfalz. 3. Jahrgang. Ausgabe 2/1993, Heft Nr. 5. Seiten 46-47.

- [41]↑Ministry of Interior, circular from 10.11.1942, loc.cit.

- [42]↑Dietrich Schabow, „Juden in Bendorf 1199-1942 …“ loc.cit.

- [43]↑Milena Bagic, „Israelitische Krankenanstalt in Bendorf-Sayn, Asyl für Nerven- und Gemütskranke, Jacoby’sche Heil- und Pflegeanstalt“, Universität Koblenz-Landau, 2015, retrieved on 26.01.2025.

- [44]↑„Sayn - Jüdische Geschichte / Jacoby'sche Anstalten“ (Sayn - Jewish History), retrieved on26.01.2025.

- [45]↑Yearly reports of Josefs-Gesellschaft, retrieved on 8.12.2024.

- [46]↑US census 1950, via ancestry.de.

- [47]↑Passenger list of Nea Hellas from 3.10.1940, Application for naturalization in the USA from 27.5.1941, via ancestry.de.

- [48]↑US census 1950 loc.cit.

- [49]↑Australian Jewish Historical Society, biography Max Schwarz (not: Schwartz), retrieved on 5.12.2024.

- [50]↑Questionnaire Max Schwarz (Fürsorge-Zentrale der Kultusgemeinde Wien) from 23.5.1938 via ancestry.de.

- [51]↑Cf. .entry Max Schwarz in „Gedenkbuch für die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus an der Uni Wien 1938“ (Memory book for Nazi vicgims at Uni Vienna) including parts of his proff of study, retrieved on 08.12.2024.

- [52]↑Wikipedia (German) about the „Anschluss“, retrieved on 20.4.2025.

- [53]↑Questionnaire loc.cit.

- [54]↑Universität Wien, „Vertreibung von Lehrenden und Studierenden 1938“ (Expulsion of teachers and students in 1938), retrieved on 10.5.2025.

- [55]↑Kitchener Camp. Refugees in Britain in 1939, registry. Retrieved on 17.5.2024.

- [56]↑Questionnaire loc.cit.

- [57]↑“Report on Internee“ Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber9906530.

- [58]↑“Report on Internee“ Max Schwarz, NAA_ItemNumber9907139. And List of internees of Camp 7 Hay Compound II, who refused to have their names passed on to the Red Cross. In NAA_ItemNumber390299, page 26f.

- [59]↑Ulrich Laufer, files of Home Office.

- [60]↑Cf. Minute of the General-Adjudant to Australian Parliarment from 29.3.1946. NAA_ItemNumber4938132, page 28, point d.

- [61]↑The unit existed from April 1942 to January 1946 . War diary of th 8th Australian Employment Company, Australian War Memorial, AWM52-22-1-17, parts 1 to 10.

- [62]↑The Australian states had not agreed on a common track gauge. It was not until 2009 that the broad gauge track was abandoned from the Albury (state of New South Wales) to Seymour (Victoria). See Wikipedia on rail gauges in Australia, retrieved on 20.4.2025.

- [63]↑The standardization of the track gauge in New South Wales and Victoria significantly reduced the role of the reloading stations and former operating locations of Tocumwal and Albury. Today there is only one track in Tocumwal. The station building houses a railroad museum and is a listed building.

- [64]↑The medical military file of Max Schwarz (erroneously Schwartz) contains the investigation files of the court martial, also concerning Ulrich Laufer, NAA_ItemNumber31554061.

- [65]↑War diary loc.cit., vol. 8 page 2.

- [66]↑Ibid, vol. 7, page 96.

- [67]↑Ibid.

- [68]↑Court martial in army files Schwarz loc.cit., page 10.

- [69]↑War diary loc.cit.

- [70]↑A detailed biography of the popular officer was published by Dunera Boy Klaus Loewald in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, retrieved on 5.5.2025.

- [71]↑Walter Pollak „Captain E.R.M. Broughton“ in Dunera News no. 24 (June 1992), page 7, retrieved on 16.11.2024.