In my childhood, Franz and Hildegard Lebrecht were “Uncle Franz” and “Aunt Hildegard” to me. Although there was no real family connection, the “informal” relationship was just as important to me – who had no other relatives – as it was to my parents Heinz and Ida. The Lebrechts were my parents’ best friends in Australia and before I was born in 1953. I can’t reconstruct how Franz Lebrecht and my father Heinz Dehn knew each other. Theoretically, there may have been points of contact as early as the beginning of the 1930s in Berlin. It is more likely that they were incarcerated in the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps at the same time or that they served together in the Australian army.

Peter Dehn, January 2024.

As a child and teenager, the author saw no reason to ask Hildegard and Franz about their lives. This article aims to make up for this omission. The fact that there is more to the lives of Franz and Hildegard than an exciting story of resistance and exile only came to light long after the deaths of all those involved.

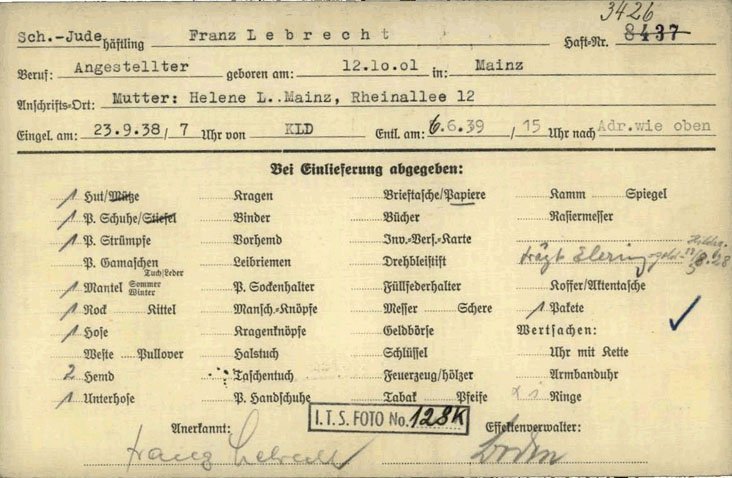

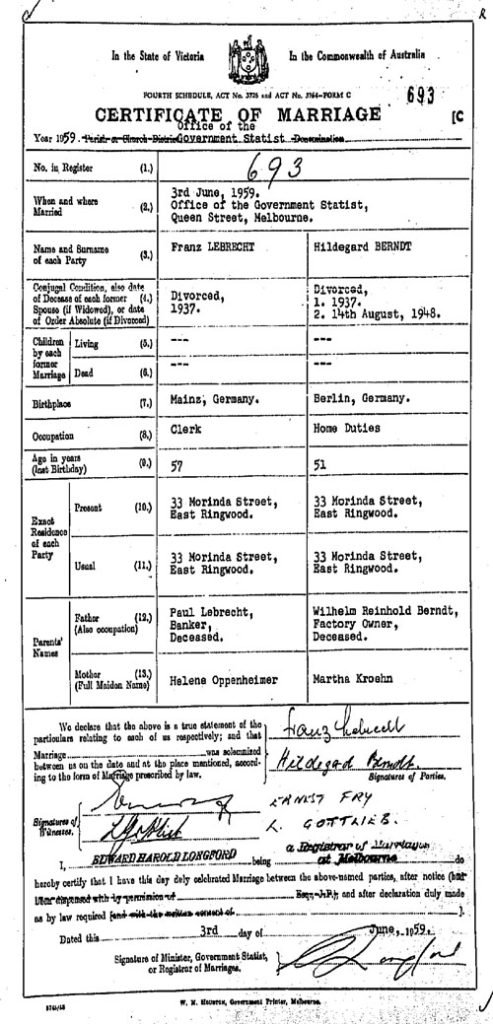

“Wears wedding ring, gold”

Franz Leopold Lebrecht[1] Registry office Berlin-Nikolassee, marriage entry no. 39 from Aug 30, 1930 and additional documents. was born on October 12, 1901 into a Jewish banking family from Mainz (Rhineland-Palatinate). His father Ignaz Paul Lebrecht[2] Registry office Mainz, entry no. 575/1865. (1865 – 1927) ran the Mainz-based private bank Lebrecht&Benfey with a partner until it was sold to Dresdner Bank in 1920. Ignaz Lebrecht married Helene Oppenheimer[3] Mappimg the Lives, File card of Terezin. in 1895. She was born in Mannheim on August 25, 1874. On September 27, 1942, she was deported from Darmstadt to Terezin, where she “died” on October 20, 1942.

Daughter Elisabeth (1898 – 1965) manages to escape to the USA with her husband Georg Durst in 1939. Franz’s younger sister Gertrud (1902 – 1981) escaped[4] Documents are available in the Dehn family archive persecution with her husband Walter and their children Ruth and Bernd to Mexico.

Franz was not raised Jewish. In an interview with the Berlin historian Hans-Rainer Sandvoß[5] Sandvoß, Hans-Rainer, handwritten notes about interviews with Franz Lebrecht from Feb 1, and March 23, 1983. Further quotations from it are not shown separately here., he reports, among other things, how his father forbade him to use Yiddish terms such as “Pleite” or “nebbich”, although these must have been part of everyday German at the time. Like many “assimilated” Jews, the Lebrecht parents probably saw themselves more as Germans than as Jews.

Franz attended the Neue Humanistische Gymnasium in Mainz from 1908 until 1920. Franz experienced the First World War as a childlike patriot, probably due to his rather conservative upbringing. He remembers that there was no school when victories were communicated, much to the delight of the children. In class, Franz has to carry the obligatory map with the front line. As the war progressed, this led to conflicts with classmates who were brought up to be even more patriotic. “Hunger only set in towards the end of the war,” Franz hints at the first contradictions to the ideal world he had experienced up to that point, which would influence his later political views.

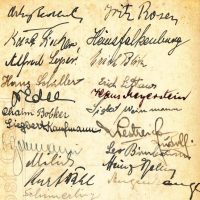

Prominent fellow graduates from his class of 1920 were Adalbert Kupferberg (sparkling wine producer) and Walter Hallstein (economic politician, “Hallstein Doctrine”). The writer Carl Zuckmayer was a well-known graduate of a previous year.

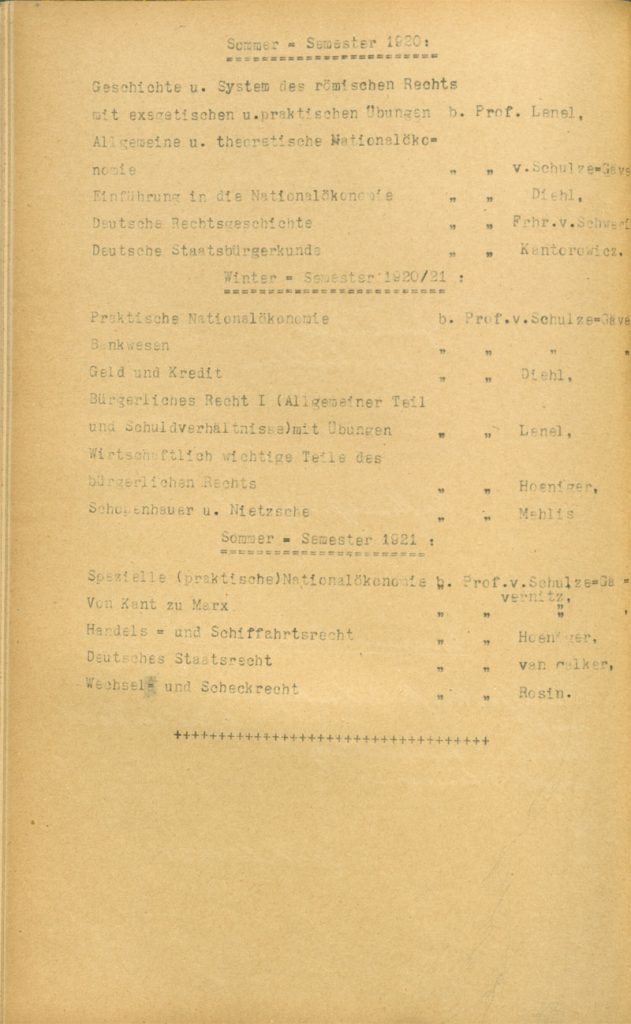

Studies and politics – connections and contacts

From 1920, Franz Lebrecht studied economics – first in Freiburg, where he was briefly a member of a student fraternity, and later in Munich. During his studies, partly under the influence of the assassination of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau in 1922 by ultra-right-wing murderers, he became politically active. As a member of the “Republikanischer Studentenbund” (Republican Student Association), he sees himself as a pioneer of socialism, but wants nothing to do with either the Social Democrats (SPD) or the Communists and renounces the right-wing, militant associations.

He spends the last six semesters in Frankfurt am Main as “no genius, no scientist”, as he says himself. He wanted to write his final thesis at Johann Wolfgang Goethe University on the eight-hour working day. He is advised that the professor and SPD member of the Reichstag, whom he has chosen as his doctoral supervisor, is an opponent of regulating working hours.

He therefore completed his doctorate in 1926 under Franz Oppenheimer (1864 – 1943) on “Der Fortschrittsgedanke bis Condorcet[6] The reprint was published 1974 by Heymann-Verlag, Göttingen, ISBN 978-3880551572.” (The idea of progress up to Condorcet). As he was unable to raise the 250 Reichsmarks required for the deposit copies, the thesis was not printed until 1934. Franz Lebrecht only found out about a reprint published in 1974 through a favorable newspaper review, recalls the Berlin antiquarian bookseller Riewert Quedens Tode[7] Dehn, Peter, interview with Riewert Q. Tode from Dec 27, 2022.. Interviewed in 1983, Lebrecht retrospectively judged his work to be an unfinished “patch-up job”. “I am smarter than a layman, but not a scientist,” Sandvoß notes one of Lebrecht’s statements. Prof. Oppenheimer, who saw himself as a “liberal socialist”, helped shape Lebrecht’s professional and political views. The two corresponded[8] No. 106 of Franz Oppenheimer’s estate register in the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, A 161. until Oppenheimer’s death[9] Lebrecht, Franz, „Bericht über Erlebnisse während der Zeit des Dritten Reiches, - u.a. aus 4 Konzentrationslagern“ (Report on experiences during the time of the Third Reich, - including 4 concentration camps) from April 10, 1960, Wiener Library, London, page 19. in the USA in 1943.

After graduating[10] Sandvoß, Hans-Rainer: „Widerstand in Mitte und Tiergarten“ (Resistance in Mitte and Tiergarten), Berlin 1999, pg 79. Dr. Franz Lebrecht found work at the Deutsche Effekten- und Wechselbank[11] Lebrecht loc.cit,, attachment page 3. in Berlin from 1927. For a time, he lived with Fritz Sternberg (1895 – 1963), whom he met in Frankfurt. Sternberg was co-founder of the “Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei” (SAPD; Socialist German Workers’ Party) in 1931 and their chief theoretician. Sandvoß quotes Lebrecht: “My political attitude was a mixture of Trotsky, Pempfert (anarchism) and Fritz Sternberg. Whenever Sternberg spoke, I went there …” And: “As a Trotskyist, I had been an anti-Stalinist since the 1920s.” Through Sternberg, Franz came into contact with many personalities from the left-wing scene. One of them was the historian Franz Borkenau[12] Ibid page 4. (1900 – 1957) from Vienna, whom Lebrecht met again in Australia in 1940.

At the bank, he met Hildegard Dora Berndt (June 2, 1907 – 1996), who came from a middle-class Protestant family in Berlin. They fell in love and got engaged on August 28, 1928, still living separately in the Nikolassee district in the southwest of the German capital. On August 30, 1930, Franz and Hildegard marry[13] Registry office Berlin-Nikolassee loc.cit. at the local registry office; they move to Berlin-Tempelhof in Attilastrasse, Hans-Rainer Sandvoß learns in conversation with Franz.

“They will never get it”

Like many others and in view of the large demonstrations of the left-wing opposition against the Nazis, Lebrecht believes “The (Nazis) will never get close”. That – and the reflection of the opposing political camps on the streets – changed suddenly on the evening of January 30, 1933: Reich President Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor and the Nazis marched on Unter den Linden in Berlin.

President Hindenburg dissolves the Reichstag on February 1, in line with the Führer’s wishes. On February 4, Hindenburg proclaims the “Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People[14] „Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutze des Deutschen Volkes“, (Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People) from Feb4, 1933, retrieved April 11, 2023.“, with which Hitler suspends elementary basic rights. Just in time for the new elections to the Reichstag and Prussian state parliament on March 5, 1933, the Nazis can begin their systematic, life-threatening persecution of political opponents, Jews, Sinti, Roma and other disagreeable groups of the population “quite legally”. The 81 seats of the KPD are simply eliminated, giving the Nazi party an absolute majority in the Reichstag[15] Cf. Wikipedia about elections of March and November 1933 (German), retrieved July 10, 2023.. The SPD is banned before the next elections; in November 1933, only the NSDAP stands as a candidate.

As early as April 1, 1933, Franz Lebrecht loses his job at the bank as part of the first wave of “Aryanization”. He finds a temporary job as a salesman; an attempt to set up a business[16] Sandvoß, interview notes loc.cit.. as an insurance agent fails. Finally, DeFaKa[17] Wikipedia about DeFaKa, (German) retrieved April 11, 2023. (Deutsches Familien Kaufhaus) employs[18] Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit.,page 79. him. The Nazis were unable to do any harm to the then cheap department store chain (in Berlin-Charlottenburg, Ranke- corner Tauentzienstraße). Its Jewish owner Jakob Michael lives in the USA and the company is registered there.

“You felt obliged to do something”

Unlike Sternberg, Lebrecht does not rely on small left-wing parties. He hoped for a change in KPD policy. “I got to know unemployed communists through the Soviet travel agency (Unter den Linden). I took part in their actions, helped design leaflets that were thrown down somewhere on Alexanderplatz[19] Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit. page 79. (from the train, Sandvoß’ note).” “I was in contact with workers from the left-wing SPD, the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP), which I was ideologically close to, and communists, I donated money, helped with writing and also received and passed on illegal writings[20] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 4. from France, the Saar region or Czechoslovakia.”

“You felt obliged to do something. We were deeply affected because the party (KPD; the communist party) did nothing. We had no idea what was in store for us if we were caught. Many KPD voters were unemployed and not ‘Marxists’, they just wanted to change the status quo[21] Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit., pages 79/80, they could have done it from the right.” “I certainly did more than the majority of German Jews, but never enough and never to the extreme. Slowly, people here also retreated and did not openly confront the enemy,” Franz Lebrecht later noted. “My activities even after 1933 up until my arrest were out of all proportion to what was still necessary and possible at the time,” he looks back self-critically[22] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 4/5. in 1960. This feeling of powerlessness led him to protest openly: On May 1, 1935, Franz Lebrecht demonstratively laid flowers for Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht[23] Ibid, page 6. at the site memorial for the in Berlin-Friedrichsfelde, which had been destroyed by the Nazis early in 1935.

Source: Federal Archives, image no. 183 H29710.

Photo: Peter Dehn.

The monument to the revolutionaries of 1918[24] Wikipedia about the memorial (German), retrieved July 20, 2023. at the Berlin-Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery was designed by architect Mies van der Rohe and inaugurated in 1926. The Nazis razed the memorial to the ground early in 1935. After the end of the Second World War, the memorial was re-established. In 1982, the GDR had the memorial stone, which has been preserved to this day, erected. Every second Sunday in January, wreaths and red carnations are laid there in memory of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and others – just as Franz Lebrecht did on May 1, 1935. He would be pleased that these tributes have survived three different political systems and that 2023 many left-wing organizations and especially young people take part in the commemoration.

Franz Lebrecht is arrested by the Gestapo on the spot. Later, in May 1935, he was taken to Lichtenburg concentration camp (now in Saxony-Anhalt). Word of the reason for his arrest got around to the SS guards[25] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 6.. They mocked him as soon as he had to give his name: “Liebknecht is your name, you Jewish bastard.”

In the concentration camps Lichtenburg and Dachau

Many of his fellow prisoners respected him for his courageous act. Among them were well-known left-wing politicians such as Carlo Mierendorff (SPD), the communists Werner Scholem and Hans Litten and the actor Wolfgang Langhoff. When the Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald concentration camps were expanded, the Lichtenburg concentration camp was rededicated to women prisoners in August 1937. Franz Lebrecht and his fellow sufferers are transferred. They are among the first 165 Jews in Dachau concentration camp[26] Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“, loci.cit., page 80.. Lebrecht arrived there on February 5, 1937, was given the prisoner number 11387[27] Reports of the KZ Dachau, retrieved April 11, 2023 via ancestry.de. and placed in hut 6. He was assigned to work in the moor. He reports on hard labor and torture at the hands of the SS guards: “January 1938. I refused to throw bricks from a wagon, the ‘Moorexpress’, at a comrade while he was still bent over and piling them up. On January 29, 1938, I was hanged for half an hour on a pole in front of the gate with my arms tied backwards. (I attribute the considerable deterioration in my posture[28] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 12. to the hard work and this incident in particular).”

Despite the terror of the SS guards, Franz stood up for his comrades in Dachau. Additional food was distributed by criminal prisoners “only to favorites”. To support the worst-off comrades, he organized a collection among his fellow prisoners: Anyone receiving more than 3 Reichsmarks from relatives, for example (up to RM 15 per week was allowed) donated 10 percent. “This guaranteed regular purchases of food, bread and spread, and fair distribution,” Franz reports. “It was called ‘Lebrecht recipients[29] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 11. line up’.”

From Dachau to Buchenwald

The authors of a biography by lawyer and communist Hans Litten note that the prisoners of Dachau hut 6 were scattered all over the world. Thus “Friedlich, Gottlieb and Lebrecht meet again in Australia[30] Bergbauer, Fröhlich, Schüler-Springorum „Hans Litten – Anwalt gegen Hitler“, Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2022, ISBN 978-3-8353-5159-2. pg 300. The three of them actually meet beforehand in Singapore.“, it says.

Franz Lebrecht was transferred to Buchenwald on September 22, 1938. During the transport, the prisoners were harassed: They are ordered to adopt particularly awkward postures so that they cannot sleep, Franz reports. He was registered in the Buchenwald concentration camp on September 23, 1938 as inmate no. 3426 and quartered in hut 23. There he meets, among others, the Social Democrat Ernst Heilmann, who is murdered in 1940, and the Communist Theodor Neubauer, he tells Sandvoß[31] Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit, page 80.. Franz also suffers from hard labor in Buchenwald; first as a water carrier, later in the quarry. In addition, criminal inmates here also hawked food and tobacco and assigned the “political prisoners” to the hardest work, including in the construction group, Franz Lebrecht reports.

On the move

Franz and Hildegard’s marriage was divorced on April 30, 1937 – a forced divorce[32] The official note from June 9, 1937 on the marriage entry Lebrecht/Berndt refers to Landgericht Berlin file no. 254 R 86.37. Documents are not available at the Court. “from my Protestant wife under pressure from the Gestapo[33] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 23.“. Franz Lebrecht probably deliberately did not stand in the way of this – if only to protect Hildegard from being stalked by the fascists. But he obviously did not want to give up the relationship completely: When he was admitted to the Buchenwald concentration camp, it was manually noted[34] Handwritten note on the personal property card index of the Buchenwald concentration camp, Arolsen archive.: “Wears wedding ring, gold Hildeg. 28/8.28” was engraved there.

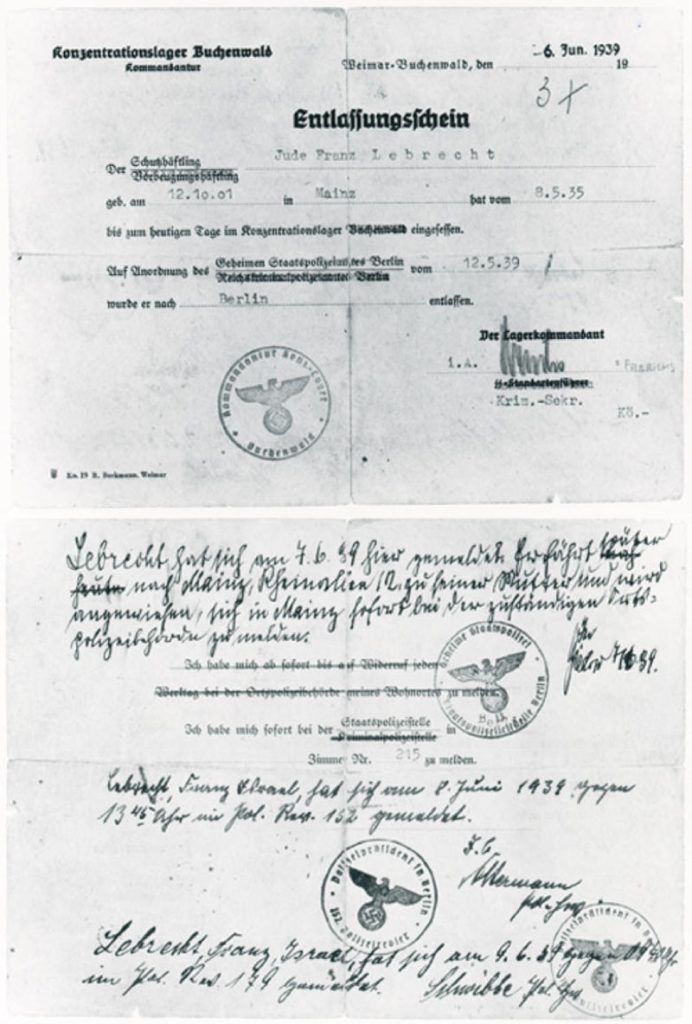

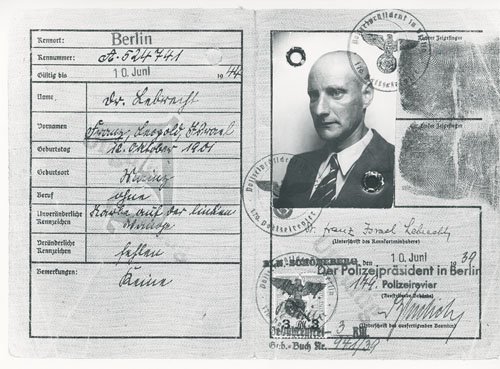

On June 6, 1939[35] Daily report of changes at Buchenwald concentration camp from June 6, 1939, Arolsen Archives., he is released from the concentration camp. As was the case for many incarcerated Jews at the time, he was told to leave Germany as quickly as possible. Permission to travel to Mainz to see his mother was refused. Franz was able to stay in Berlin for ten days and was obliged to report to the police every day. With the help of friends and relatives, he manages to meet Hildegard again – only in secret, sometimes in a cab, sometimes in the back room of a bookshop. This is also where he reconnects with his concentration camp comrade Carlo Mierendorff. “I remember that we went to a small pub near the Skala late in the evening, where Carlo introduced me to the landlady as ‘returned from the desert’. I was then asked by the landlady to consider myself her guest[36] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 24..” This story makes it clear how small – and yet very courageous in the face of the threat of draconian punishments – resistance could be.

Exile in Singapore

Franz Lebrecht received his passport from Adolf Eichmann[37] Here memory is most likely deceiving: it was only in October 1939 that Eichmann became head of the Nazi’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Berlin's Kurfürstenstrasse and head of Department IV D 4 ("Eviction Matters") of the RSHA. He was previously stationed in Prague and Vienna. Cf. Wikipedia about Eichmann, and Jewish emigration (German), retrieded May 15, 2023. personally at Kurfürstenstraße 115/116 at the Gestapo’s Jewish department, he later remembered. His mother Helene Lebrecht and a brother-in-law financed a ship passage to Shanghai, where no entry visas were required. Franz Lebrecht starts the journey in Genoa on the Gneisenau. The Jewish passengers are seated together at tables on the sidelines. The other passengers are indifferent to them. Franz remembers that only one of them is an NSDAP rabble-rouser.

Even before setting sail, Franz reports, he realized that he did not actually want to go to Shanghai: the Nazi press had gleefully reported that Jews could not live there in freedom. His intentions were thus fulfilled when two former concentration camp inmates brought him ashore with the permission of the authorities on his arrival in Singapore on July 6, 1939.

He reports on the first part of his exile: “I lived in Singapore with my friend, a dentist, Dr Ernest Frey[38] See Lebrecht loc.cit., page 25. The dentist adopted the anglicised name Fry (not Frey) in Australia. …” Lebrecht and his hosts Ernst and Margarethe Friedlich “had one meal a day[39] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 25., which consisted of a cheap dish for two from the Chinese quarter”.

Franz Lebrecht is lucky and gets an office job at a gold mine in Singapore. On September 15, 1939, he was transferred from there to Pahang[40] Pahang was part of the former Federated Malay States (FMS), which were under British control. Today it a federal state of Malaysia. (Malaysia) to work at the Tui Gold mine. The comparatively normal life in Malaysia lasted almost exactly one year. Expecting a Japanese invasion, the British promised the Jews who had fled to Singapore a life of freedom in Australia. 266 mostly Jewish refugeees[41] Inglis K., Spark, S. et al, "Dunera Lives – Profiles" contains a list of Queen Mary internees, page 463f. in Singapore believed this and set sail on September 18, 1940 on the luxury steamer Queen Mary, which had been converted into a troopship. For a week, they are treated as normal 2nd class passengers[42] Cf. Dunera Association, retrieced April 11, 2023.. The journey is only an “evacuation” in appearance. The 269 people were interned[43] National Archives of Australia (NAA), Entry form for Franz Lebrecht. NAA_ItemNumber9904209. in Singapore and were guarded on board by 42 men from the Gordon Highlander Regiment. The British promise of freedom was a lie, as they intended to have these Nazi persecutees locked away in Australia.

Australia: Once again behind barbed wire

After landing in Melbourne on September 25, 1940, the Queen Mary group suffers the fate that the Dunera Boys experience: The 269 people find themselves in Camp 3 Tatura near Shepparton (state of Victoria) behind triple barbed wire and under military guard. Like the camps for the Dunera boys in Hay, this camp is also financed by the British. There are eight barracks in each of four compounds, separated by barbed wire and guard posts. The Queen Mary group is separated: families, some with very young children, and women traveling alone are placed in Compound C. Franz Lebrecht and 64 other “single” men are housed in Compound D[44] Cf. Radok, Rainer "Von Königsberg nach Melbourne", Lüneburg 1998, ISBN 9783932267154, Chapter XI., which they shared with some Dunera boys.

As in the concentration camp, Franz Lebrecht also worked for the community behind Australian barbed wire. He was elected to the internees’ “Council of Honor” and had to calm down squabblers, among other things. Tatura is Franz Lebrecht’s last place of detention. For him and all Jews and anti-Nazis, his time behind bars ends in the course of 1942.

Since August 1940, the British government has been the target of harsh public and parliamentary criticism for the internment and deportation of refugees. The scandals surrounding the Dunera’s trip and the sinking of the Arandora Star contributed to this. More than 1,000 internees from the Dunera and Queen Mary are prepared to serve in the British Pioneer Corps or other war-related activities and return to England[45] Inglis K., Spark, S. et al aao, page 18. between June 1941 and July 1945. However, four of these ships are lost in torpedo attacks; among the victims are 47 ex-internees[46] Major Layton in an undated interview, quoted from Bartrop/Eisen, page 101.

On “defense line 70”

“In January 1942, we were released from internment on the condition that we volunteered for the Australian army,” is how Franz Lebrecht describes the start of the next chapter in his life. Heinz Dehn, Leon Gottlieb, Ernst Friedlich and a few hundred other internees also decided to do so. After all, army service is a prerequisite for a residence permit or naturalization in Australia.

The 8th Australian Employment Company is something special: the soldiers in this unit are recruited exclusively from Jewish ex-internees. Franz describes the disappointment of most of them: “I myself, who had already volunteered for the front with about 3 men during the internment, said with bitter irony: ‚We are defending the 70th defense line[47] Lebrecht loc.cit., page 27.‘”. The Nazi opponents were not allowed to fight, but replaced the conscripted Australians in the economy.

The main field of operation for the “Eighth” is the railroad. Due to different track gauges in Australia’s federal states, reloading has to take place at their borders. Franz and his comrades mainly do this in Albury, Australia’s largest gauge change station[48] Wikipedia about railways in Australia (German), retrieved April 11, 2023. on the border of New South Wales and Victoria. Franz Lebrecht’s personnel record sheet states that he joined the service on April 19, 1942. He was promoted to Lance Corporal as early as June 23 and was able to sew a patch on his right jacket sleeve. He was posted to Albury, Tocumwal and Bendigo and was discharged[49] Lebrecht, Franz, army files NAA_ItemNumber 6255287. from service on February 5, 1946.

Further down under and in plain clothes again

Franz Lebrecht’s first job after the war and in freedom and independence was with two Dunera Boys, whom he probably met as a soldier. The designer and sculptor Fred Lowen[50] Inglis K., Spark, S. et al aao, pg 288 ( Lowen was wrong about location "Shanghai"). (Fritz Löwenstein) “decided to make his woodworking profitable by sharing the work with Franz Lebrecht, a German socialist who had been imprisoned in Dachau and ended up in Shanghai in 1940, only to be interned there and then sent to Tatura on the Queen Mary.”

In 1946, Fred Lowen founded a furniture company with Ernest (Ernst) Rodeck, a Dunera Boy from Vienna, whose name The Fler Co[51] ABC Radio, manuscript "Fler and the Modernist Impulse" from Feb 27, 2011, retrieved April 12, 2023. consisted of their initials. Lowen and Rodeck design modern, timeless furniture from Australian woods. This challenge to the heavy, dark and uncomfortable furniture of the British-colonialist style that was widespread in Australia was their recipe for success. Fler was invited to exhibit in the Australia Hall at Expo 1967 in Montreal, Canada.

In 1948, Lebrecht also names The Fler Co as his employer and assistant turner[52] Lebrecht, Franz, Certificate of Registration from Feb 20, 1948, NAA_ItemNumber 5705375. as his occupation. Possibly at the company – at the time still a small stable in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond – Franz injured his upper body, Riewert Tode[53] Peter Dehn, interview with Riewert Tode loc.cit. assumes. The rib fracture does not heal properly; what remains is a slightly bulging ribcage. At the end of 1948, Franz Lebrecht officially describes himself as a textile worker at the company United Woolworks[54] Lebrecht, Franz, Certificate of Registration loc.cit. on Sturt St. in South Melbourne.

And he becomes politically active again: while still serving in the army, he collects money among the soldiers for the Australian campaign “Sheepskins for Russia[55] As a result the Red Army received 400,000 skins and 40 containers with medicine and medical equipment, see "Russia and Australia: 75 Years of Cooperation" from Jan 22, 2018, retrieved April 12, 2923.“. Lebrecht recalls[56] Lebrecht loc.cit. page 29. that this was a success not so much because of the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union, but because of the support from politicians and business people. After the end of the war, he became involved “with a few friends” in the “Movement for a free Germany” founded in Mexico. In Melbourne, Dunera Boy Heinz Zantoff was one of the editors of a small spin-off magazine[57] "Anti-Nazi Information", published by The Free German Movement Group in Australia. 2 editions in the German Federal Library, signature ZB 16168<a>. Editor was Dunera-Boy Heinz Zantoff until his return to Germany end of August 1945.. “I remember (as a factory worker who spent exactly 50% of my net income on parcels, but couldn’t afford new clothes) that in some cases I did the shopping, packing and shipping for others because they were so heartless and convenient,” Lebrecht criticizes[58] Lebrecht, loc.cit., page 30. wealthy Australian Jews.

A reunion

The most remarkable date for Franz Lebrecht in Australia is certainly July 4, 1949: “I would like to mention that after years of searching and unavoidable delays, my divorced wife came to Australia as my fiancée – after 14 years of separation.” It is hard to fathom what lies behind this rather casually closing remark[59] Lebrecht, loc.cit., page 31. in his contribution to the Wiener Library. Was Franz still wearing the wedding ring with the date of their engagement? After Hildegard’s arrival on the SS Toscana, she moves in with Franz at 23 Landsdowne Road[60] Berndt, Hildegard, Certification of Registration from July 4, 1949. National Archives of Australia, NAA_ItemNumber 5705376. in the East St. Kilda district.

A job for panel buildings á la Melbourne

On Hildegard’s advice, Franz takes a job as a clerk at the “Concrete House Project[61] Lebrecht, Certification loc.cit.” of the “Housing Commission of Victoria” from early 1950. This state-owned company plans and builds low-cost apartments from prefabricated concrete elements using its own factory. It manages and rents out the apartments. This eliminates slums and creates good, affordable housing for poor and large families.

To this day, the project’s high-rise buildings tower far above the low eaves heights common in Melbourne suburbs such as Windsor and Carlton. At the end of the 1960s, however, there was criticism of the associated urban sprawl. The project was abandoned in the early 1970s. The photos rightly evoke associations with the new housing estates in the GDR, where the housing shortage there was not tackled until 1969[62] The GDR decided an "Einheitssystem Bau" (Unified Building System) in April 1969, retrieved April 14, April 2023. with the help of standardized prefabricated buildings until 1990.

The second marriage

Hildegard and Franz waited ten years until the next step in their “new” life together: on June 3, 1959, one day after Hildegard’s 52nd birthday, they married[63] Registry office Victoria from June 3, certificate of marriage, file no. M-UCI-D2; NAA_ItemNumber5705375 and NAA_ItemNumber5705376. for a second time in Melbourne. Two of Franz’s friends from his time in the concentration camp, Singapore and internment sign as witnesses: Leon Gottlieb, like Franz, also comes to Australia on the Queen Mary. Ernst Friedlich and his first wife Margarete were first interned by the British in Singapore on January 25, 1941 and arrived in Sydney on the Boissevain on February 8, 1941, to be taken immediately to Tatura Camp 3. There they met their friends Franz and Leon again.

Back in Berlin

One month after their wedding, on July 6, 1959, Franz and Hildegard board the British ship Orsova to leave Australia and the Commonwealth for Germany[64] Official notes on marriage certificates NAA_ItemNumbers 5705375, 5705376. for good.

West Berlin is their destination, as Franz’s political convictions mean he cannot accept a life in the GDR. They find their first accommodation in the well-known neighbourhood of Nikolassee in the south-west of the half-city. They rented a room in Mrs. de Ahna’s villa at Prinz-Friedrich-Leopold-Straße 45 and later moved to Wilmersdorf. Their small two-room apartment in a new building is at Sächsische Straße 69[65] The Dehn family visited the Lebrecht’s several times at both places.. Hildegard’s last apartment in Berlin was 1949 at Sächsische Straße 21[66] Entry files fo Australia from July 4, 1949, NAA_ItemNumber5705376..

“A living book” on the trail

Franz Lebrecht is as well-read as he is an obsessive collector of books. This is already evident in the concentration camp documents. When he was sent to Buchenwald, he had to deliver a package. His release papers show that he took four books from it during the course of his imprisonment. He donated a fifth book to the inmates’ library[67] Property card of Buchenwald concentration camp from June 5, 1939.; the title of the work has not survived.

“He has a nice library”, Dunera boy Rainer Radok[68] Radok, loc.cit. later recalled of the acquaintance, which had its roots in Tatura Camp 3. Radok’s brother Uwe writes in his diary[69] Jacquie Holden, Seamus Spark „Shadowline. The Dunera Diaries of Uwe Radok“, page 93. about the politically interested group of people into which Franz introduces him: “I met one of Lebrecht’s people, hpe there will be more. That at least is a society which holds some prospects, mot those people one seems to have outgrown, together with the feeling of hours in bourgeois comfort and uneasiness in a dark, dreary sub-station.”

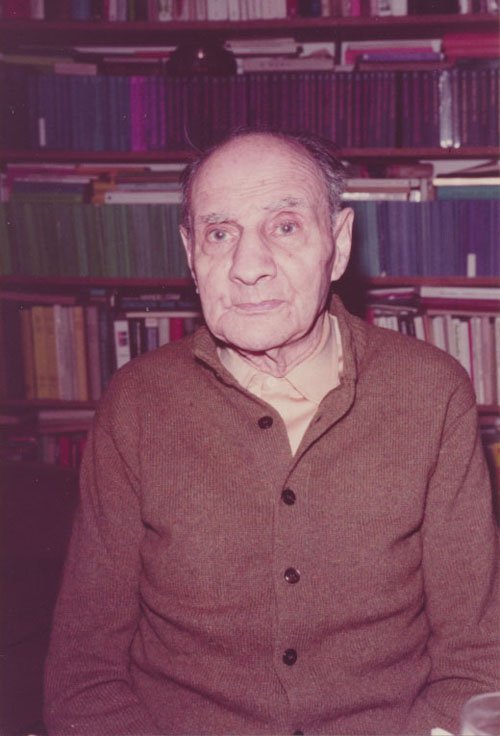

The Berlin antiquarian Riewert Quedens Tode and Franz Lebrecht met at Tode’s former workplace in the early 1970s. The tiny left-wing bookstore “edition et”, specialized in art books, happening and Fluxus literature, is located in the basement of the Europa Center in West Berlin-Charlottenburg. “He was the only customer who had an open account. He could take any book with him without paying straight away. We wrote down the price and he paid at the end of the month”, says Tode[70] Peter Dehn, Interview loc.cit., remembering the first time they met. “I got to know him as a somewhat stooped but very sprightly old gentleman who always carried a bag of books with him on his right and left. He carried these heavy book bags every day, even though his doctor didn’t allow him to carry anything heavy.” From around 1971 onwards, Tode supported Franz in organizing the increasingly extensive library for an hourly payment.

Franz regularly visits certain coffee houses, bookstores and antiquarian bookstores. He is well known in the circle of left-wing booksellers in West Berlin. “I know from colleagues that he had such a ‘trail’. I have never met anyone who was such a book person. He was, so to speak, a living book.”

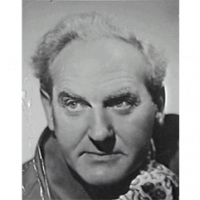

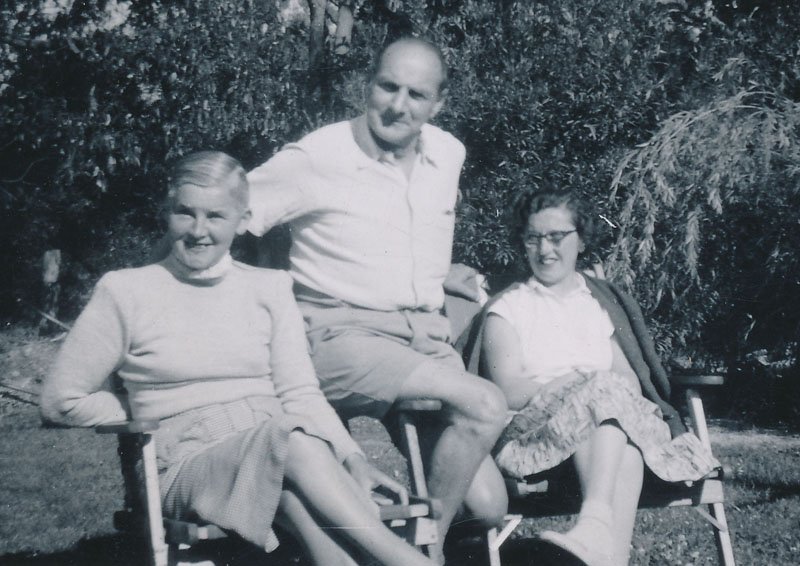

Hildegard and Franz Lebrecht with Ida Dehn (from left) in the 1960s, probably in the garden of the deAhna villa. Source: Dehn family archive.

Books, books, books

Hildegard is not very happy with Franzen’s passion for books. She wants to prevent the small apartment from turning into a library. It still allows for a small shelf. Tode’s brother Harboe later remodels it so that it can accommodate three rows of books deep down. Because that is far from enough for Franz, he rents “at least three” (Tode) unused cellar sheds from neighbors. “It was dry and there was light. The cellars were full of shelves and it was so narrow that there was no reasonable distance between them.” He rents another “book room” in the apartment of a deceased friend in the house opposite.

That’s not enough either. Franz Lebrecht becomes a subtenant with many books in the shared apartment where Riewert Tode lived at the time. She lives in a former pharmacy on the Schöneberg so called “Red Island”. Franz stores his books in old pharmacy shelves and cupboards. One day, a roommate’s carelessness causes a smoldering fire. Franz Lebrecht happened to be on his way there and met the fire department towards the end of the operation. Riewert Tode tells what Franz reported to him: “When I stood in front of the house on Roßbachstrasse and saw the fire department, I knew it was about my books.” The damage is rather minor. Tode describes Lebrecht’s reaction: “He went in through the back door instead of the shop door, sat down in the kitchen and had philosophical conversations with the fire chief – as he called him.”

Lebrecht had, among others, given the Historical Commission of the West Berlin Social democrativ Party several truckloads of books (Tode) for viewing, which were later purchased there and auctioned off after Lebrecht’s death. He irregularly supplies a friend in Munich with packages of books in order to build a library for his children. Since 1959, a shipping company in Hamburg has stored three sea chests containing books that the Lebrechts had brought with them from Australia. It never happened to bring them to Berlin during Franz’s lifetime. Riewert Tode was only able to view and take over the book boxes after Franz Lebrecht’s death. As expected, 90 percent of them were English-language titles. There are still a number of copies from this estate in the inventory of the Antiquariat Tode.

Politically active again

Franz Lebrecht never renounces his left-wing political stance, which he himself describes as “Trotskyist”. He continues to take a keen interest in political events, reads several daily newspapers and can be found at many demonstrations in the 60s and 70s. He became one of the first members of the West Berlin “Republican Club”, founded on April 30, 1967. This association, which emerged from the student movement, offered the numerous left-wing groups on Charlottenburg’s Wielandstrasse near Kurfürstendamm a meeting place and a platform for debates. The concept became a model for similar institutions in West Germany, but only lasted for a short time.

The Dehn family and other friends pay tribute to their friend Franz’s passion for books: Heinz Dehn was a heavy smoker. The silver paper from the cigarette boxes is collected in the Dehn house “for Uncle Franz”. If a cigarette or chocolate pack is thrown into the trash along with the silver or gold paper, there will be scolding. As soon as a meeting with the Lebrechts has been arranged, bookmarks made of silver paper are folded and bundled over a few evenings. One or two books from the Lebrecht estate that are still in the Tode antiquarian bookshop still have such bookmarks sticking out of them today.

Franz Lebrecht dies on October 30, 1983 in Berlin. He is buried with his wife Hildegard, who died in 1996, in the Berndt/Lebrecht family grave at the Heiligkreuz Cemetery in Berlin Mariendorf.

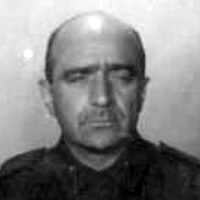

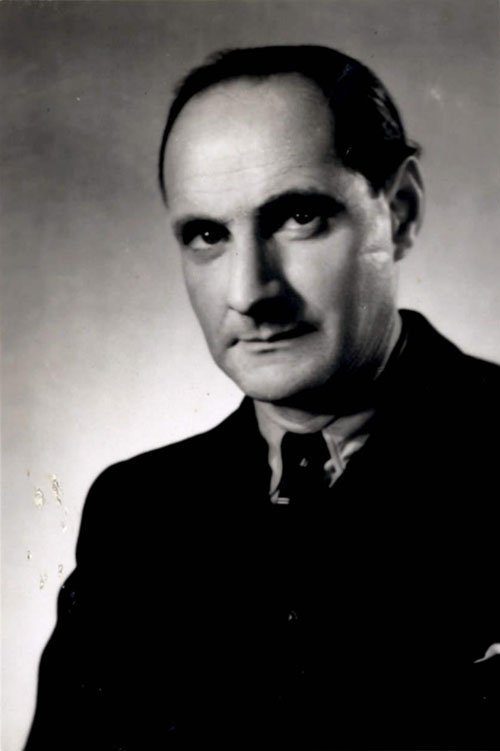

Franz Lebrecht 1980 Source: Archive Tode.

Addendim: How to avoid compensation

In the early 1950s, Franz Lebrecht and his sisters Elisabeth Durst and Gertrud Scheuer jointly applied for compensation for the economic damage suffered by the Lebrecht family from their exile countries of Australia, Mexico and the USA. Having been fobbed off with a small amount, they sued in Rhineland-Palatinate in 1957 for restitution for the furniture in their parents’ apartment, estimated at 70,000 Reichsmarks. Her mother Helene was forced to leave the apartment without being allowed to take any furniture, etc. with her. The legal dispute that followed the decisions of the responsible authorities in 1957 only ended in July 1964 with a judgment that even demanded repayment from the plaintiffs: the expulsion from the apartment due to the anti-Semitic laws and the associated ban on disposing of the property, is not an expropriation at all. This was only implemented through a later official decision. However, this was only made out after the house was completely destroyed by a bomb attack. Consequently, according to the judges, the family does not lose their property due to Nazi injustice, but rather due to enemy warfare. The verdict becomes final because the siblings are tired of further international activities after years of fighting.

The judgment[71] Judgement of the Compensation Chamber of Landgericht Mainz from July 13, 1964, file no. 5 O (WG) 60/62 pages 10/11. Archives of Rhineland-Palatine, signature wJ 10 No. 9804. Adittional cases: J 10 No. 6568 und J 10 No. 7051. contains the following sentence about the situation in 1942, which cannot be adequately described as “cynical” in view of the restricted everyday lives of Jewish people due to state bans: “The Jewish residents of German cities lived very withdrawn back then.” For Franz’s mother, “withdrawn” looks like this: Helene Lebrecht was deported from Darmstadt to the Theresienstadt ghetto[72] Mapping the lives, retrieved April 14, 2023. on September 27, 1942 on transport XVII/1-595. The date of her death is known to be October 20, 1942.

The repeated complaint from the regional court from November 1957 to the Mainz Restitution Office “about the delayed sending of the administrative files” for 18 proceedings, including the one mentioned first by the Lebrecht siblings, also shows how reparation is hindered.

Please note: The author would like to thank Hans-Rainer Sandvoß for providing his notes of his interviews with Franz Lebrecht and other documents. The section on Franz’s childhood and studies is largely based on these. Equally heartfelt thanks go to Riewert Quedens Tode, who was available for an extensive interview and provided photos and documents from the Housing Commission of Victoria from the Lebrecht estate. Further sections of this article are based on Franz Lebrecht’s autobiographical report which he wrote for the Holocaust Archive Wiener Library in London in early 1960.

Footnotes

show

- [1]↑Registry office Berlin-Nikolassee, marriage entry no. 39 from Aug 30, 1930 and additional documents.

- [2]↑Registry office Mainz, entry no. 575/1865.

- [3]↑Mappimg the Lives, File card of Terezin.

- [4]↑Documents are available in the Dehn family archive

- [5]↑Sandvoß, Hans-Rainer, handwritten notes about interviews with Franz Lebrecht from Feb 1, and March 23, 1983. Further quotations from it are not shown separately here.

- [6]↑The reprint was published 1974 by Heymann-Verlag, Göttingen, ISBN 978-3880551572.

- [7]↑Dehn, Peter, interview with Riewert Q. Tode from Dec 27, 2022.

- [8]↑No. 106 of Franz Oppenheimer’s estate register in the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, A 161.

- [9]↑Lebrecht, Franz, „Bericht über Erlebnisse während der Zeit des Dritten Reiches, - u.a. aus 4 Konzentrationslagern“ (Report on experiences during the time of the Third Reich, - including 4 concentration camps) from April 10, 1960, Wiener Library, London, page 19.

- [10]↑Sandvoß, Hans-Rainer: „Widerstand in Mitte und Tiergarten“ (Resistance in Mitte and Tiergarten), Berlin 1999, pg 79.

- [11]↑Lebrecht loc.cit,, attachment page 3.

- [12]↑Ibid page 4.

- [13]↑Registry office Berlin-Nikolassee loc.cit.

- [14]↑„Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutze des Deutschen Volkes“, (Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of the German People) from Feb4, 1933, retrieved April 11, 2023.

- [15]↑Cf. Wikipedia about elections of March and November 1933 (German), retrieved July 10, 2023.

- [16]↑Sandvoß, interview notes loc.cit..

- [17]↑Wikipedia about DeFaKa, (German) retrieved April 11, 2023.

- [18]↑Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit.,page 79.

- [19]↑Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit. page 79.

- [20]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 4.

- [21]↑Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit., pages 79/80

- [22]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 4/5.

- [23]↑Ibid, page 6.

- [24]↑Wikipedia about the memorial (German), retrieved July 20, 2023.

- [25]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 6.

- [26]↑Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“, loci.cit., page 80.

- [27]↑Reports of the KZ Dachau, retrieved April 11, 2023 via ancestry.de.

- [28]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 12.

- [29]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 11.

- [30]↑Bergbauer, Fröhlich, Schüler-Springorum „Hans Litten – Anwalt gegen Hitler“, Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2022, ISBN 978-3-8353-5159-2. pg 300. The three of them actually meet beforehand in Singapore.

- [31]↑Sandvoß, „Widerstand …“ loc.cit, page 80.

- [32]↑The official note from June 9, 1937 on the marriage entry Lebrecht/Berndt refers to Landgericht Berlin file no. 254 R 86.37. Documents are not available at the Court.

- [33]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 23.

- [34]↑Handwritten note on the personal property card index of the Buchenwald concentration camp, Arolsen archive.

- [35]↑Daily report of changes at Buchenwald concentration camp from June 6, 1939, Arolsen Archives.

- [36]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 24.

- [37]↑Here memory is most likely deceiving: it was only in October 1939 that Eichmann became head of the Nazi’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Berlin's Kurfürstenstrasse and head of Department IV D 4 ("Eviction Matters") of the RSHA. He was previously stationed in Prague and Vienna. Cf. Wikipedia about Eichmann, and Jewish emigration (German), retrieded May 15, 2023.

- [38]↑See Lebrecht loc.cit., page 25. The dentist adopted the anglicised name Fry (not Frey) in Australia.

- [39]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 25.

- [40]↑Pahang was part of the former Federated Malay States (FMS), which were under British control. Today it a federal state of Malaysia.

- [41]↑Inglis K., Spark, S. et al, "Dunera Lives – Profiles" contains a list of Queen Mary internees, page 463f.

- [42]↑Cf. Dunera Association, retrieced April 11, 2023.

- [43]↑National Archives of Australia (NAA), Entry form for Franz Lebrecht. NAA_ItemNumber9904209.

- [44]↑Cf. Radok, Rainer "Von Königsberg nach Melbourne", Lüneburg 1998, ISBN 9783932267154, Chapter XI.

- [45]↑Inglis K., Spark, S. et al aao, page 18.

- [46]↑Major Layton in an undated interview, quoted from Bartrop/Eisen, page 101

- [47]↑Lebrecht loc.cit., page 27.

- [48]↑Wikipedia about railways in Australia (German), retrieved April 11, 2023.

- [49]↑Lebrecht, Franz, army files NAA_ItemNumber 6255287.

- [50]↑Inglis K., Spark, S. et al aao, pg 288 ( Lowen was wrong about location "Shanghai").

- [51]↑ABC Radio, manuscript "Fler and the Modernist Impulse" from Feb 27, 2011, retrieved April 12, 2023.

- [52]↑Lebrecht, Franz, Certificate of Registration from Feb 20, 1948, NAA_ItemNumber 5705375.

- [53]↑Peter Dehn, interview with Riewert Tode loc.cit.

- [54]↑Lebrecht, Franz, Certificate of Registration loc.cit.

- [55]↑As a result the Red Army received 400,000 skins and 40 containers with medicine and medical equipment, see "Russia and Australia: 75 Years of Cooperation" from Jan 22, 2018, retrieved April 12, 2923.

- [56]↑Lebrecht loc.cit. page 29.

- [57]↑"Anti-Nazi Information", published by The Free German Movement Group in Australia. 2 editions in the German Federal Library, signature ZB 16168<a>. Editor was Dunera-Boy Heinz Zantoff until his return to Germany end of August 1945.

- [58]↑Lebrecht, loc.cit., page 30.

- [59]↑Lebrecht, loc.cit., page 31.

- [60]↑Berndt, Hildegard, Certification of Registration from July 4, 1949. National Archives of Australia, NAA_ItemNumber 5705376.

- [61]↑Lebrecht, Certification loc.cit.

- [62]↑The GDR decided an "Einheitssystem Bau" (Unified Building System) in April 1969, retrieved April 14, April 2023.

- [63]↑Registry office Victoria from June 3, certificate of marriage, file no. M-UCI-D2; NAA_ItemNumber5705375 and NAA_ItemNumber5705376.

- [64]↑Official notes on marriage certificates NAA_ItemNumbers 5705375, 5705376.

- [65]↑The Dehn family visited the Lebrecht’s several times at both places.

- [66]↑Entry files fo Australia from July 4, 1949, NAA_ItemNumber5705376.

- [67]↑Property card of Buchenwald concentration camp from June 5, 1939.

- [68]↑Radok, loc.cit.

- [69]↑Jacquie Holden, Seamus Spark „Shadowline. The Dunera Diaries of Uwe Radok“, page 93.

- [70]↑Peter Dehn, Interview loc.cit.

- [71]↑Judgement of the Compensation Chamber of Landgericht Mainz from July 13, 1964, file no. 5 O (WG) 60/62 pages 10/11. Archives of Rhineland-Palatine, signature wJ 10 No. 9804. Adittional cases: J 10 No. 6568 und J 10 No. 7051.

- [72]↑Mapping the lives, retrieved April 14, 2023.